Funeral dinner at the Elks Lodge, Blackfoot, ID. Self-portrait,

Digital photograph, iPhone filter, 2021

On two separate occasions, an ambulance whisked my wife’s sister from Blackfoot, Idaho to the University of Utah Hospital in Salt Lake City, Utah. About a four-hour round trip, if you speed at 85-90 mph. The second trip confirmed what most had been expecting after the first, “…there wasn’t anything more they could do for her.”

The end still came suddenly. A few weeks was the prediction, but after three days of palliative care, she passed away overnight in her house where three generations of children called it their home.

After the funeral, we head towards the Elks Lodge for her final reception held in her honor. She and her husband were club members for as long as I have known them, going back to 1996.

In 2005, you could see by his pallor, drained of all color, that his time was not long. He needed a heart transplant. A degenerative heart disease killed the father in his late thirties and the fate train was not stopping for the son to get off.

When I saw him next, he was practically jumping around. I jokingly asked if he was not part of the control group and got a monkey’s heart instead. The transplant extended his life a few more years, but with complications. Many of them arise between trade-offs of opposing forces. Eventually an inoperable brain tumor, the result of immunosuppressive drugs preventing his cells from devouring the foreign organ, hollowed out the part we knew as him and left a void in our hearts.

To go through his excruciating ordeal is like the myth of Sisyphus, punished to endless toil for cheating death. Was the punishment befitting the crime? He was a man of few words.

Even as the centrifugal forces gained strength to unravel and disperse him, he beamed like a pulsar, the remnant of a once mighty star, whenever any people he loved orbited into his field of vision.

I never felt he regretted his decision. What little extra time he would get was his, and the rest given to medical science.

Prior to his heart transplant, the hospital where the surgery took place provided housing for out-of-town recipients. At the time, one of the facilities was located at the mouth of Little Cottonwood Canyon near Sandy, Utah. The first time my wife and I drove there to pick him up and ferry him to an appointment, our mouths dropped. This facility was a compound with four identical, large, nondescript rectangular houses with a 6 feet tall or taller opaque fence encircling the complex.

When he steps out of the house, he motions us to come up. By our dumbfounded look, he says, “It’s what you think it is.” It turns out; the former property owners were polygamist, but not just any polygamists. The property owners were the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (FLDS) led at the time by Warren Jeff, who is now serving a sentence of life plus 20 years in a Texas prison for sexual assault of a minor.

The no-nonsense house is functionally organized with the largest space reserved for the kitchen. As you go through each building, just like the outside, you discover they are identical inside and disappointing. I guess I was expecting weirder. However, revulsion sets in once I comprehend, these are not so much about homes and families (bigger and merrier), but human husbandry — Monday is barn 1, Tuesday is barn 2, and so on. Dehumanizing individuals as cattle, life perverted.

We gather at the Elks Lodge down in the multi-purpose hall. It appears, on this occasion, management allowed sunlight onto the premises. However, decades of smoke, sweat, and booze deposited on the rug rise up like specters of human folly to haunt your nostrils. Weirdly, the place maintains a timeless 1970-80s “Deer Hunter” movie-like excuse for a private bar. It is a gentleman’s club for the non-land gentry type, where muscles pay for the booze and sweat leaves a tip.

I am standing in front of a makeshift photo booth. It is a simulated wood-siding panel, painted white with plastic flowers stapled to it and draped over the top as if it was a Kentucky Derby winner. Not pushed far enough into the corner to be out of the way, I am unsure if built specifically for this occasion or a holdover from a dance night. I hardly see anyone stopping in front of it, let alone give it much of a glance. I quickly take several photos until I arrive at one I do not look like I have a triple chin, and nonchalantly continue the circuit between the food and bar.

I am not one to take many selfies. I am not sure why I did, except maybe on the off chance, one of her daughters involved with the funeral planning would ask, in a group text, if anyone had taken a photo with the “garland of roses” and if so, would they send them a copy.

After midnight, my wife and I head back to Salt Lake City. The night sky is starless and moonless, no other streetlights around, and few, if any, cars on the road. It is disorienting, and slightly stressful. Even with our truck’s high-beam headlights on, you are never sure if wildlife will suddenly jump out into the road.

In the mid-nineties, I visited Spiral Jetty, a famous 1970 land-art by Robert Smithson on the edge of the Great Salt Lake. At sunset, driving back on a dusty dirt trail knifing across an otherwise uninterrupted field of Utah wild sunflowers, jackrabbits would randomly poke their head up near the side of the road and dash madly across in front of the car.

Instead of continuing, they dart and scamper up the trail, and they either turned off to the same side or not. I panic and attempt to avoid them. However, their unpredictable frequency and the risk of ditching the car in the middle of nowhere, I decided to keep straight and did not look back in the rearview mirror. The suicide jackrabbits are locally well known.

My wife begins retelling something my sister-in-law shared with her. Her sister believed she would outlive my wife despite her own frail health.

Her sister started out as a farmer’s daughter when chemical farming was the rage and dust storms were nothing but a little kick up. At seventeen, she was pregnant and a farmer’s wife. In the late 1970s, big agribusiness and banking loan practices swarmed like locusts and decimated the smaller and financially fragile farming communities. She and her husband lost their third-generation farm.

He would land a job with the University of Idaho managing the research potato fields. Free from the burdens of the annual loan repayments for seed and equipment purchase, the reduced stress extended his life. She eventually worked, until her retirement, at a Simplot plant manufacturing fertilizer and fire retardant. I remember her laugh always cut short, hijacked by a racking cough.

My sister-in-law formed this life expectancy opinion because my wife has cancer. Diagnosed in April 2015, she underwent eight weeks of chemotherapy, a mastectomy including thirteen lymph nodes removal followed by six weeks of radiation. The aggressive treatment left the scars of an all-out war permanently written across her battle bruised body.

In October 2019, the cancer returned from its hiatus and ended up slumming outside of her ureter near her left kidney. Initially, the oncologist team thought, possibly bladder cancer. The breast cancer was double positive (estrogen/progesterone) and this was double negative and signet ring shaped.

She escaped any lasting harm to her kidney, and spared a bladder removal thereby avoiding permanent bilateral nephrostomy tubes and bags. After her principal oncologist successfully argued on her behalf to the insurance company to approve the immunotherapy treatment, it ended early due to an adverse liver reaction. She has been on an oral pill.

Recently, the cancer marker is rising, and the mass inside is growing despite the increased chemo dosage. She has escaped much of the side effects, but with the higher dosage, they are unmistakable. She is easily fatigued and constantly wheezing with shortness of breath. She is in bed nearly 24 hours a day. She starts an IV drip alternative in a few days. I am relieved for the change despite the unknowns.

Before the treatment change, I plotted the cancer marker growth rate. If allowed to progress, it will surpass the previous cancer number in seven years. I am not expecting the growth rate to stay well behaved.

My wife occasionally quips a line from comedian George Carlin. I paraphrase. “I don’t know why they call it premature death. No one really knows when someone is going to die, so how can it be premature?”

She informed me, death holds no fear for her. She will decide the cost of living.

Unexpectedly, she starts singing.

Is that all there is

Is that all there is

If that’s all there is, my friends

Then let’s keep dancing

Let’s break out the booze and have a ball

If that’s all there is

Is That All There Is? – Peggy Lee, 1969

The self-made lighted disco dance floor with music synchronized

LED at The District 2017. Digital photograph, iPhone filter, 2022

AFTERWORD

I worked the summer of 1994 as a scenic artist transforming a western town to look more Hollywood western for a TV period movie. Film production comes to Utah, if not for the scenery, then for the cheap labor of non-union workers. Working 6-day weeks for 12-14 hours a day are the privileges granted by our right-to-work state. The grind was not all dust and nails. As a transplant to Utah, the commute between Park City and Morgan was postcard-like for someone who had not yet seen ‘real’ scenery.

The production goes crazy in July with a week left until filming starts with the set half built. Before High Definition (HD) TV, the scenic work is only a facade as the background is usually out-of-focus. Two days before the film crew arrives, everyone works thirty-six hours, sleep eight, and work another sixteen.

Our crew chief quits the project, placing my employment in question. My crew friend insists we drive to Park City so he can pick up his paycheck. The stretch of highway between Morgan and Park City was lonesome and with July’s scorching heat plus little sleep, it is inevitable, we would both nod off only a mile to the exit speeding close to 90 mph.

I was startled awake from metal hitting metal. I ask who hit us, and I hear, “Oh shit!” repeatedly. We hit another car and went off the road. Miraculously there were no road signs, no guardrails, no fence posts and no ditches to do horrific damage.

We check on the other driver. He is a little shaken up, but none worse for the wear. He says when he looked in his rearview mirror; he thought to himself, “They are going awfully fast.” Before he could react, we hit.

It so happens, going 90 mph for us but 75 for him, the impact speed is only 15 mph. The high-speed bump slowed our vehicle from catapulting into the field. The production company refused to cover the accident as it was off the clock. Two weeks of pay evaporated like sweat drops on a scorching asphalt from towing fees between Park City to Salt Lake City, and the repairs.

I receive an invite to the “End of the Production Wrap Party” in September to be held in Park City. There will be a live band, food and an open bar. I show up determined to make up for my friend’s pay loss.

At the bar, my wife’s friend introduces us. The band was so loud I did not say much. She loves to dance, easily attracting attention around her. I had drunk sufficiently to overcome my shyness and joined her dancing group. I might have smiled a little. After the band’s final encore, we exited together and gathered with the other drunkards milling about just outside.

The remaining heat rising off the street warms our group as we ping pong down Main. I happened to look up, and marvel. The mountain air was so clear I thought I had telescoping eyes. The Milky Way majestically unfurled with breathtaking clarity. I felt cosmic kinship to my primordial ancestors.

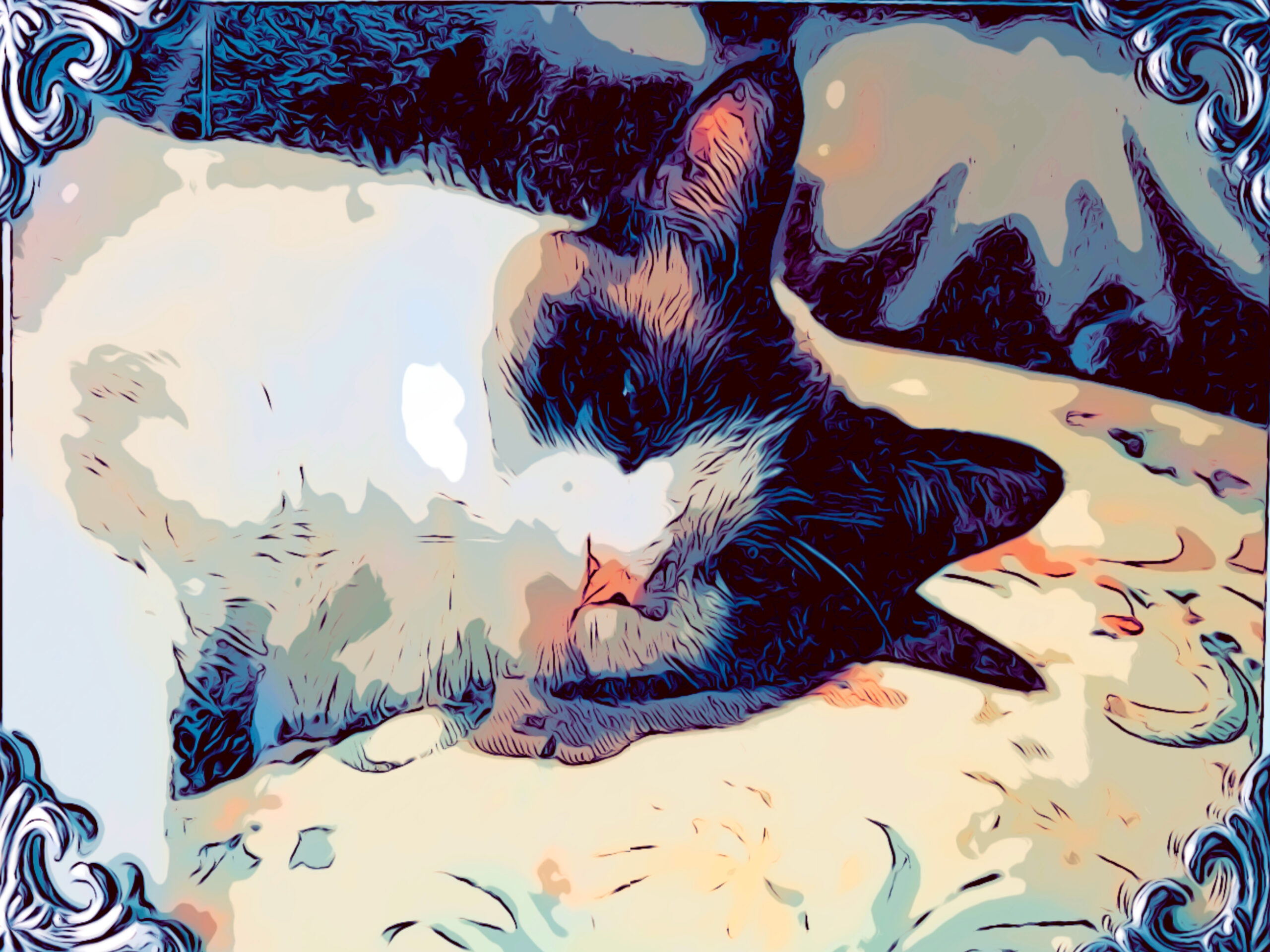

After a year of dating, we moved in together. I was freelancing while booting up an art career, and so worked from home. As a “house husband”, I was in charge of two cats, Miles and Shadow, and her daughter, 4 years old. Miles would die from kidney disease, and we harbored guilt believing our indecisiveness caused him needless suffering.

Like his namesake, Shadow was a constant companion. He loved greeting and giving generous affection to everyone. He changed my opinions of cats and I learned invaluable lessons about unconditional love. When old age immobilized him, I feared what his absence would sunder.

I fiercely held tight. A 3-night stay at the veterinarians, then at home, injecting water under his skin 5 times a day, while hand feeding what little he would eat. Later, I would be furious at the veterinarian office for one, pressuring me to have “emergency” care for a blind and immobile 17-year-old cat, and two not counseling about unreasonable expectations for favorable outcomes

after the care.

At the time, that was far from my mind. I retreated to my wife’s place with Shadow. I stayed every day and repositioned him following the sun throughout the house. He knew every spot, as he loved the heat. So much so, he could sleep within a foot of the gas furnace flames.

One morning while drinking my coffee, I look over at him when he makes an effort to rise. I picked him up, and brought him over onto my lap. I gently comforted him. I delayed going back to work for as long as I could. Eventually, I nestled him in his bed over the radiator, said I would be back and closed the door behind me. When my wife got home, she called to say he had

passed away.

During this period, my wife and I were living separately. We did not seem to want the same things and our life stalled. She asked if I was unwilling or unable. I explained my blockage. Imagine we had walked across an expansive plain, and then suddenly come upon a ravine with a slackline spanning the abyss. She on the other side beckons me to her. Gripped by fear, I am unable to cross.

I took Shadow’s death hard. It flung open locked drawers of childhood emotions. I had an unhealthy mistrust of relationships from fear of abandonment. Orphaned as a baby, adopted at 5 years-old and my adoptive parents separated two years later.

Three years would pass before I could think about another cat. In the interim, under the aegis of my wife’s limitless love, I undertook healing journeys for my early trauma, classes for personal responsibility, and read the book Iron John by Robert Bly. His insights about male development in the absence of male role models resonated with me. My tool bag was missing much.

My wife and I reunited and we bought a house. Our family moved in. She insisted that my stepdaughter and I adopt two kittens from the rescue shelter.

They were magical. I discovered I could love them just as intensely, and have room for more. I would experience the heartache of loss again, as each would pass away, one hit by a car and the other never found. She would insist we adopt again.

I return to the present. Surrounded by our two recent additions Queen Diane and Duke Dragon to our Kingdom of the Noble Cats of Stroudd Land. In between the chemo changeover, the side effects have subsided and she is unencumbered by pain. We all watch spellbound by her dancing. My wife is a joie de vivre, lifting my furrowed brow of worry.

Wake me up before you go-go

‘Cause I’m not planning on going solo

Wake me up before you go-go (ah)

Take me dancing tonight

I wanna hit that high (yeah, yeah)

Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go – Wham, George Michael, 1984

Shadow 2003, King of the Noble Cats of Stroudd Land. Digital photograph, iPhone filter, 2022