Elemental

Fire

It starts in the duodenum

Dilly-dallying innocent little girl don’t you know you’re in

Brambled thickets sticking in thin skin

Kindling for your pyre.

Kick those scrawny snarling legs

cat fight little wolf

those teeth sharpen quick but not enough.

Loops through the belly button retro-endo-up inside

warm coals hissing in anticipation

one more phrase

Spark and I’ll blaze pouring out of my

ear canals

Sop down drop through the piriformis to the heels

Stomp the wrongness out of you

and sip the wine spoiled juices make.

Earth

Steady is the hand that

holds others up when prostrate

I am tipped skyward in prayer

to a faith built on shaken foundation.

Immutable, that’s what you are

steadfast, stubborn ox

knows everything of service and nothing of self.

Dumb beasts forge blindly

But battering rams were built to break

Charging head-first, loosing horns

Have they noticed that the most rigid structures

Undergo the most extreme destabilization?

Air

You sailed across peaks

Running along mountain ridges in whisper white stockings

to find me

Huddled in the feather light embrace of another.

How do you reckon Little lungs swell with no training

While large lungs stutter?

Breathe to blow

Fill the spaces between ribs with

Bubblegum bubbles

Shrink and stretch each breath.

Tripping through hair and dancing along the creases you left

Dented in my palms.

Go where the wind takes you, they say

But I am rooted in soil.

Water

Arms wide open, I ran towards, but she barreled across my outstretched fingertips

Crying, I asked why, she

wiped tiny streams from my cheeks and told me to try again.

It’s a fine line between float and sink, there were moments when I thought we were

finally working

But tides change and so do you.

Did you like how I looked, with coins adorning my eyelids, chains nestled in my bedrocks?

I will teach my children how to swim, to paddle with currents.

You changed so I did too.

And I did too.

Elegy-Gratitude to the Anonymous

It is apparent that it is time to transition

A vessel that once held thoughts fears & ambitions

Has become something much more tranquil and silent

As they reflect on their life; joyful and vibrant

It may appear their journey is complete

But by choice they will not fall obsolete

When their vibrant sun has finally set

Their face for many will be impossible to forget

For many young students brimming with promise

The health of future generations weighs heavily on us

Against the plagues of disease we are armed

We hope to learn, to heal, and to do no harm

We learn not only by books and lectures

With time we become masters of the body’s architecture

And through the great sacrifice and selflessness of our fellow man

Full of life and experience long before our stewardship began

These hands which once held the hands of a family member or lover

There is so much more to their life than we can possibly uncover

This face that once laughed, cried, and smiled

The scars and joys of their life sit before us compiled

This privilege has been bestowed upon us students of health

To seek healing and community rather than wealth

So that we may change and save lives

To become individuals with the power to revive

This face I peer into each and every day

Yet unfortunately to whom I will never be able to say

Thank you for your donation to me

For your face is in every patient I see

Illness Narratives

“Restitution stories attempt to outdistance mortality by rendering illness transitory. Chaos stories are sucked into the undertow of illness and the disasters that attend it. Quest stories meet suffering head on, they accept illness and seek to use it.” (Arthur Frank, The Wounded Storyteller, page 115)

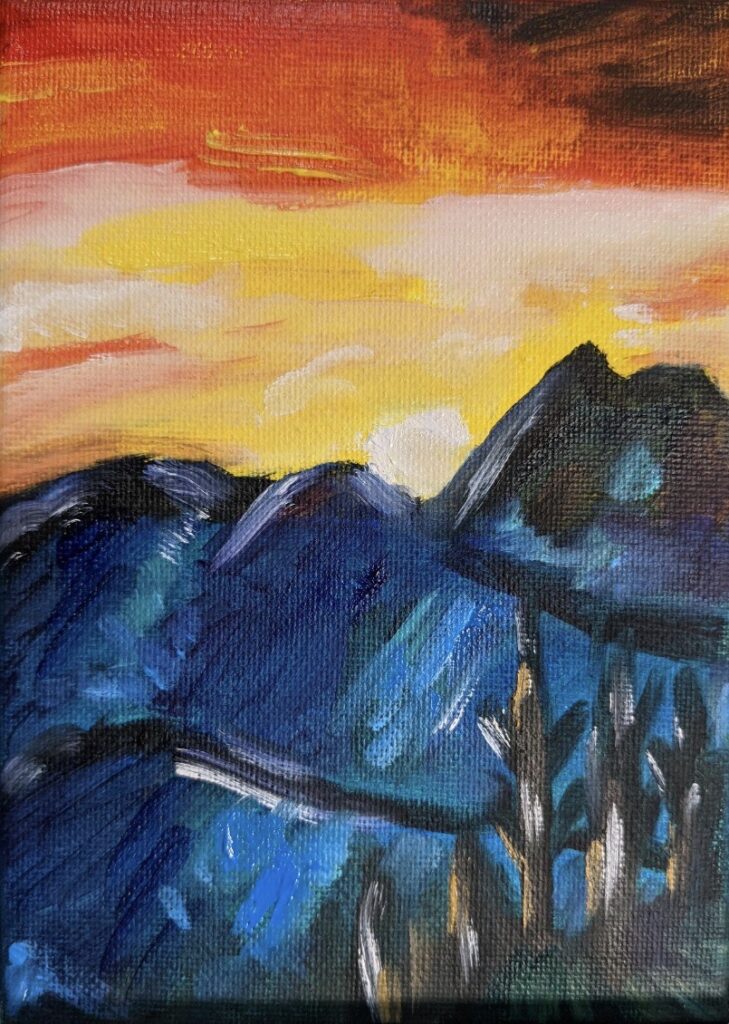

This painting attempts to capture the emotions behind the three forms of illness narratives, which are arranged in a triptych or three-part series to emphasize the central importance of the quest narrative. Looking at illness as narrative helps us be more understanding and compassionate, as we recognize themes inherent in their view of suffering. These paintings also tell an overarching story of loss, chaos, confusion leading towards healing and transformation in the setting of a forest fire. These are oil paintings on canvas.

The chaos narrative has blood-red undertones, which peek through some of the thinner layers of paint and depicts a forest amid a raging wildfire. The bleak black, gray, and brown trees are illuminated solely by the light of the fire which consumes them. During the chaos narrative, there is no time to describe your distress; there is only living it. You are swept along by the ferocity of the illness and feel that you have lost control and choice. It is terrifying. It feels as if it will never end. It’s almost impossible to see the future.

The restoration narrative has bright green and yellow undertones, which add to the joyous, happy feeling of the sunrise over the burned forest. Despite the tragedy which occurred, the sun is rising, and a new day is dawning. The trees in the foreground still stand, though badly burnt. There are still dark clouds in the sky, but there is feeling of hope in the air. During the restoration narrative, you feel as if everything will return to normal soon, that the illness will be put behind you, and that all will be well.

The quest narrative depicts the transformation of the burned forest as new life begins to grow in the fertile soil laid by destruction. Flowers and grasses are beginning to grow at the bases of the crumbling burnt trees, adding beauty to a desolate landscape. During the quest narrative, you find purpose in your suffering and feel that illness becomes a transformative time. As a phoenix rises from the ashes, your illness-induced transformation changes your perspective, your story, and perhaps your values and ideals.The quest narrative is realistic, yet hopeful that there is meaning to suffering.

Understanding the patient experience as they experience aspects of one or all of these illness narratives is key for a physician. Patient narratives are complex but thinking of them in this framework can help increase empathy and understanding.

These paintings were created following conversations in the Letters of Medicine Elective, Radical Listening at the End of Life with Dr. Susan Sample and Dr. Jenny Wei.

Peering Over the Edge

One Halloween in grade school, my parents solicited the help of my three younger siblings and I to paste “vote yes for life” cards on candy bars to hand out to trick-or-treaters. I now realize that words like “pro-choice” and “pro-life” do not represent the emotional weight or humanity of a patient’s decision to have or not have an abortion.

In July 2021, I had used the copper IUD for 8 months. I became increasingly nauseated since my wisdom teeth were removed two months prior. When my period didn’t come when I expected in July, I decided to quell my anxiety and get a pregnancy test at Intermountain.

A nurse did the pregnancy test in front of me and told me it was positive. Time seemed to stop. I heard myself blurt out that I wanted an abortion. I admire how she handled those moments. She gave me a few moments to process what was happening and offered kind reassurance. She walked me to the front desk to schedule an appointment with an OB/GYN later that day. We were in the waiting room at the check-in station, and I was scared others would overhear. I felt embarrassed. She used the phrase “elevated hCG with copper IUD” at the front desk, which gave me a wave of relief. I was grateful that she maintained my privacy.

I drove home absolutely devastated and terrified. I tried to calm myself down, but I remember crying on my kitchen floor, feeling overwhelmed, scared, and alone. Later I went back to the clinic and learned that the pregnancy was 8 weeks. The gynecologist removed my IUD and explained that she had to send me somewhere else because she wasn’t allowed to give me the mifepristone and misoprostol needed for a medication abortion. Throughout the whole process, she was so kind and supportive. She gave me a phone number for a local Planned Parenthood, and I left. The abrupt send-off was the first glimpse of stigma I encountered. I called the number and learned about Utah’s online informed consent module that I would need to complete before a 72-hour waiting period. Additionally, I found out that the first available appointment to see an abortion provider in Salt Lake was a month out.

I called my partner on the way home, again feeling a wave of relief as he listened to me and offered his care and support. At this point, I had done enough research to know that at 12 weeks I may not be able to have a medication abortion. This could limit my choices to vacuum aspiration or D&C less than a week before medical school started.

At home, I started the informed consent module. I was startled by the high-definition images of various stages of pregnancy and smiling babies staring back at me from my laptop. About halfway through, I recognized that someone thought they had the right to shame me into making me feel bad about myself and my actions. At that moment, I realized how wrong it is to coerce or shape an individuals’ choices by imposing judgment on them.

I’d had enough. I shut my laptop and called the main Planned Parenthood number. My worries seemed to vanish as the caring person on the phone helped me find an appointment for the next day in Fort Collins. I threw my overnight stuff in a bag and called my partner to make sure he could come with me.

Within an hour, we were driving to Colorado. We found the cheapest motel we could find. Throughout the night, I heard yelling and fighting outside. The smell of cigarettes and grease from the burgers & fries we grabbed for dinner permeated the stuffy room. I felt ashamed and filthy, inside and out.

I was making an irreversible decision. This was the first time I would do something that I certainly couldn’t take back in any tangible way. A sense of grief mixed with consolation surfaced as I contemplated how my life would be altered by my choice. The following day, we got up early to take a walk before the appointment. Arriving at the Planned Parenthood, we were greeted by anti-abortion picketers. I again felt dirty, the shame bubbling up from my gut as my heart raced. Since the pandemic was still ongoing, I went in alone with the security guard for my appointment. I had another ultrasound, and this time I took the picture. I was touched that the staff asked if I would like it, even though I was there for an abortion.

I talked with the physician and felt relieved and comforted for the first time. She reassured me that we could take care of both the abortion and getting another birth control that day. I went back to the car to complete consent over the phone and learned what to expect with the medications. I took the mifepristone at the clinic and brought the misoprostol home to use later.

The next day, I took the four misoprostol tablets by placing them between my teeth and cheeks on both sides of my mouth. About an hour after taking the medication, my ears started ringing, and my apartment seemed to wobble slowly.I crouched on my bed in a child’s pose position with a hot water bottle. My partner comforted me as we watched TV.

I am so glad that he was there with me. His presence let me know that I was not alone. I felt lots of cramping and a bit faint. Periodically, he would help me get to the bathroom. A couple of hours later, I felt much better. While he went out to bring back some ice cream, I passed the pregnancy. I stared into the toilet bowl, stunned and unsure of how to think or feel in that surreal moment. Then, in classic medical student form, I decided to take a photo and make sense of it later.

I spent the next day with a close friend. We talked about everything that had happened, which helped me feel content. That evening, I tried to box up my feelings and ignore the grief that I was convinced I could skip over. It made everything worse. My partner and I cried together. We were confused, frustrated, and upset, feeling like we had been ill-prepared for the aftermath of our experience despite having no regrets. I spent time getting in touch with friends and family for the rest of the week. Later in July, I went on a long backpacking trip with friends, proving that I could find the strength to recover from my shame. On the way back, I spotted a tiny kitten on the side of the road and brought him to a shelter.

Things continued to be complicated. I cried through most of my first semester, especially during embryology. I questioned if I was a killer. Did my actions mean I was a bad person? Pictures of classmates’ families and children made me wonder what it would be like if I had chosen differently. Through all of the ups and downs, I never had regret over my decision. Instead, I had grief.

I am so grateful that I had the resources and support to decide that having a child at that time would not serve the child’s quality of life or my own. Without my car, my savings, my insurance, and my family and friends, I may not have had timely, safe access to abortion and social support during the time after.

Since my experience, I have become more attuned to the stigma surrounding abortion. Abortion is not is for irresponsible or “bad” people. Abortion is for everyone in our society, a tool that gives individuals the power to determine what is best for themselves, their families, and their communities.

I believe it is critical for those working in healthcare to recognize that because countless individuals have experienced traumatic events, we must be thoughtful about how we communicate with patients to prevent further harm.We must honor the privilege of caring for individuals amid life-changing situations. We must come alongside the patients we serve, respecting their values, privacy, and autonomy as they make challenging decisions.

In the Shallows

My father was a professor of biology. His children were his first students. He taught us about skyscraping redwoods, legged tadpoles, predator and prey, newborn lambs and afterbirth. He took us outside and showed us what creatures do to survive.

Even on the day in 2012 as we waited for the doctor’s call confirming his cancer diagnosis, Dad helped my husband Peter and I plan a day outdoors—a canoeing excursion down Big Springs, the headwaters of the Snake River. We had to be back by four, when the doctor said he’d call, so we got up early. We drove until farmland became mountain meadows bordered with pine trees, the grass a little dry in the August sun but green by the river, which was clear and bright, washing every pebble copper-clean under dark, fishy shadows.

It was a near-perfect float: no storms, no punctured rafts to patch with chewing gum and row frantically to the end of the course. Only sunshine, white clouds, icy water splashed from boat to boat by hand and through plastic pistols. We welcomed the water’s bite, my seven-year-old brave with a paddle, my four-year old’s giggles trickling toward the sky.

One small disaster: little Sara, a family friend, stood up in her canoe and fell into the river. “I’m going under the boat!” she screamed, her lifejacket’s shoulders up around her temples, her hands clawing the hull as her feet kicked at the keel. My mother leaned over to pull her out of the water and the boat lurched to one side, making Dad, who’d been reaching from the back, lose his balance and fall in the water too.

There was no real danger. Sara needed only to stand up in the shallows and lift her head above the surface. The water came to Dad’s thigh, where the tumor inside twisted between muscle and bone.

But Sara’s panic called to that which skirted our own thoughts, keeping pace with us downstream. Watching us from the forest’s shadows like a cat.

#

That afternoon, Peter and our two children went to Sara’s family’s house, leaving me with my parents and my brother Shaun. The idea was that we’d be stronger in this sphere of nuclear family, while possibly shielding the kids from grief, new and raw.

After the doctor called, Mom and I went to the computer room to look up the words he’d given us: stage three sarcoma. We read about the treatments—radiation and surgery—and the prognosis. Dad walked in as we scrolled to a paragraph that discussed amputation. He sat, reading silently over our shoulders. Together, we stared at the screen.

Then Dad stood and said, “Well, I guess I’ll go mow the lawn.”

We didn’t look at him as he left. “Is that OK for him to do?” I asked my mother. Dad had Parkinson’s disease too. She shrugged, as if to say he’d do it anyway.

While Dad pushed the droning mower outside—slowly—my mother and I made cherry Danishes in the kitchen, because we needed to. We put on bright patterned aprons, mixed powders and pastes in a frenzy of sugar and flour, glaze, and gooey red pie filling. We tasted everything as though we hadn’t before and might not again.

My brother Shaun, useless as chef but genius as DJ, put on the new Daft Punk album, turned it up loud, and the three of us danced. I remembered a couple of disco moves from a dance aerobics DVD, and Mom tried to teach us the hustle. After a while, we heard silence outside in the seconds between songs. Dad had finished the lawn and would come in soon. When we heard the back door open, our dancing slowed, our eyes fixed on the entryway. Would Dad understand our meager mourning riot?

Dad entered the room in rhythm, thrusting out his neck, one hand on his head, the other outstretched, his legs marching in time to the music. It was an old impression of a water-dwelling bug that he used to do for his biology classes, and we cheered for him, relieved.

We danced for a while, as we used to when Shaun and I were children, when we were certain our parents would always dance with us, when we overestimated how many drum beats it would take to arrive at whatever came next.

My husband doesn’t like films in which a family dancing in their kitchen is presented as their “happily ever after.” But sometimes it’s all you can do: let the electronica vibrate down behind your sternum, fill the beats up with swinging hips and kicking feet, mouth full of cherries, head full of Snake River memories, hands full of other hands.

#

Once, I cleaned the back balcony of our apartment on a quiet weekend. At the time, Peter and I had two kids, a dissertation, and a job, so things had been piling up out there: a table, an easel, various toys, a fold-out cot with squeaky springs. Everything was covered in dust and grit from the parking lot. The bent aluminum of the cot creaked as I opened it to wipe down the vinyl mattress.

Then I saw them. A family of daddy-long-legs. The mother’s legs stretched three inches across, her young piled among them, white, each as large as a thistle head, but fragile—I’d already crushed some—with legs as fine as the hairs on my arm. They made the delicate, oblique movements of newborns. I felt the mother had been saying something important to them, and I had cut her off mid-sentence.

“Caleb, come see this!” I called. My son didn’t answer. He was watching cartoons, getting over a fever. His cheeks were pink and his damp hair curled at his temples. My husband dozed on the couch next to him, his feet on the coffee table. One hand rested on the book turned over on his chest, and his other arm held our daughter, her small fingers opening and closing on his skin, her lips parted as she slept.

They were all safe, sleepy and well-fed. The four of us had mostly avoided hospitals and poisonous arguments, collected our paychecks and kept most of our sanity. We rested in the shallows, riding the slow river down…but for how long? Were the aspens and pines already whipping by, invisible on the banks around us as the river twisted, carrying us toward an unmapped destination? Would we be able, there, to keep hold of each other?

On my dusty balcony, the arachnid mother seemed to look up from her half-lit home of warm decay and ask what was next. I paused: the creatures were so wispy, so insubstantial, it would have been easiest to wipe them away and wash my rag afterward.

Instead, I lifted the cot over the side of the deck, leaned over, and blew. The mother caught the wind first. Two more breaths and her children followed in clumps, like dandelion seeds wafting down into the grass. They remained there for a minute, tangled bits of confused lint, before dissolving from my sight into their brave new world of blade and dew.

#

For eight years after the river, for eleven years after the balcony, my family drifted in blessed shallows.

But today, I kneel in my garden, watching a mother wolf spider. She clutches a huge egg sac that falls away as she skitters from my trowel. The sac is round and white, a miniature golfball, an excised tumor. I have two of those growing in my right breast, maybe more. I learned about them in a digitized report this morning while sitting with my husband on our bed. The bright July world glares with this fact. Incomprehensible, jagged fractals of what-if spiral through my mind, my heart, my belly.

I herd the spider back to her sac. It takes minutes. Can’t she sense it there, in front of her? Why don’t her many eyes catch on this most precious object, one she built using her body’s paper, string, and grit? Why won’t she hold on? Why can’t she feel my need for her to be able to bear her children away?

At last she snatches the cradle with her spinnerets and journeys under the fence into the next yard. Relieved, I watch her go.

A brown mouse bears witness from among the weeds. He’s the one who’s been sneaking into the pantry through the fireplace at night, enjoying our warmth, our bounty for too long. Next week I’ll trap him and let him loose in the mountains, a place he has never once seen.

#

Two days later, my daughter splashes in a pine-ringed lake in the Uinta hills. She just turned twelve. Since the 2020 pandemic rolled over our state four months ago like a slow-moving tsunami, she and her brother have each grown an inch. Maybe two.

She lifts a stick covered in pondweed. “I’m just going to play in the shallow part until everyone else gets here.”

Drowning, I nod from my camp chair on the sand. Please, God, let her enjoy the shallows today. She’ll know about my diagnosis in a week, but first, her birthday streamers need time to come down. I don’t want her to think of cancer every year as she blows out her candles. She looks like a woman in her new tie-dye bathing suit, but I worry that her pubescent mental fettle is as delicate as the bodies of the newly-hatched darkwing beetles she keeps in her room. I wait on the beach, holding a scream under my tongue.

Aunts arrive, uncles arrive, cousins and friends arrive. Mom and Dad pull up in their SUV laden with kayaks and life jackets, and I help them unload. Dad stumbles on the gravel path. Every autumn, an MRI machine rolls the protons of his body to divine whether he can live another year drifting in the quiet water near the edge of an illness waterfall, never knowing whether cancer or Parkinsons will carry him over.

My parents have taught me how to live without screaming. They are still here. Today, so am I.

Peter and I row small, separate crafts across the lake. The aunties’ chatter, the cousins’ laughter grows softer as they shrink into the distance, their voices blending with the liquid sounds of lapping water and birdcall. Peter reaches a hand toward me over the green depths. We sparkle and break like glass.

I think of dancing in the kitchen eight years ago. Here we are again, in the deep. Again, we heed the music playing around us, knowing this song won’t last forever.

Any second a new one will start.

Blindspotting: The Father and The Imam

The term in the title?

Means I’m revealin’

Biases that triggered

Growth because I want

My delta to be that of

The Nile

You Muslim?

Asks The Father

I hold my breath,

Firmly rooted.

Been cut before.

To care for you,

Means to care for me.

Islam is me.

As-salamu Alaikum, Habibi.

Responds, my friend.

Is There Nothing More That I Can Do? -A short story by a family physician

This story actually begins years before I started practice in my rural community. It began when I was a 3rd year medical student. There was a phrase that I would occasionally hear from my attending and/or resident physicians when I was on my inpatient clinical rotations. Mostly I recall hearing this phrase on my surgery rotation where I had been assigned to the trauma surgery team at our local county hospital.

Anyone who works as a first responder (police, fire and ambulance), or has had medical or nursing training in a large county hospital will completely understand this setting. But, for most of the public, such an understanding would be truly foreign.

Large, urban, county hospitals usually have a designation as a Level I Trauma Service. This is the highest designation given to a hospital which has extensive equipment and staffing to handle any type of trauma. In a large city, there would be a wide variety of serious and often frightening cases that would come to a Level I Trauma hospital; for example; shootings, stabbings, rapes, assaults, motor vehicle accidents, drug overdoses, and any number of accidents (e.g. serious falls), and major medical emergencies including heart attacks and strokes.

Every case that we would receive through the emergency room received the highest standard of care available. We always had priority for any lab or X-ray needs, the blood bank was always on stand-by to provide necessary transfusions, and there were always operating rooms available for emergency surgeries. But, even with the best care, not every patient was destined to survive, as you can imagine given the severity of these types of cases.

Some patients died even as we were trying our best to save them. Others survived their emergency care, yet would die in the coming days from the severity of their injuries (major burns, massive trauma from an automobile accident, massive stroke or heart attack). Others would die from the predicable complications that were a result of their injuries, despite the fact that we were always checking for these to occur. The most common complications seemed to be overwhelming infection, continued hemorrhage, or major organ shutdown (kidney failure, liver failure, heart failure).

I consider myself to be a caring and compassionate individual, and I cared deeply about the welfare of our patients. I quickly learned that for those who were conscious, they appreciated a visit from one of their physicians (patients felt like the whole team consisted of physicians, even though some of us were still medical students), beyond the team rounds that were held every morning. I had the privilege of learning something about our patients’ lives and would share their hopes and fears. Ironically, because I would take the extra time to get to know many of our patients on a more personal level, my attending faculty surgeons would refer to me as the team’s “psychiatrist!” I know that they considered that reference to be a bit of an insult, but I considered it to be a compliment!

As we cared for these patients who were suffering the most serious complications from their emergent event, it would be clear that a specific patient was just not going to survive. I first heard the phrase while we would be making our rounds on those patients. The phrase was (and still is); “there is nothing more that we can do for this patient.”

To be fair to my trauma surgery teachers (attending and resident physicians), this phrase was used on other clinical services for terminally ill patients who were dying of their heart disease, or lung disease, or cancer. I am quite certain that during those years, I learned to use that phrase, too. I still felt a sense of sadness and loss when these patients died, but I was comforted knowing that we had done all that we could do, and perhaps my personal interactions added something positive at the end of their lives.

Later, as a resident physician in family medicine, working in a community hospital, we had a much less serious set of patients under our care, but we would still occasionally be dealing with a terminal situation. Once again, I recall an occasional attending/consulting physician telling the resident staff that “there was nothing more that could be done” for a specific patient. Sometimes, there is an underlying message that goes with that statement. The message is that we would be wasting resources and causing prolonged suffering for a patient and their family by trying to prevent the inevitable. I believe that is a valid concern that requires discussion with the family on a regular basis and, hopefully, being able to refer to an Advanced Directive from the patient themselves.

Now, allow me to jump forward to the time when I was practicing family medicine in a beautiful, small, rural community, so that I can share a patient’s story that taught me a most valuable lesson.

I want to tell you about Autumn (not her real name, of course), and I will not offer a fictionalized last name. I had heard quite a bit about Autumn during my first two years in this community. Although she was not a patient of mine (at least, not yet), many of my patients had told me about her. They would talk about the nature walks that she led through the forest in our area. She would teach about the various plants and creatures living in the forest and whether certain plants had any nutritional or medicinal value. I had patients who would much prefer an herbal remedy from Autumn, than a prescription for a pharmaceutical product from me!

I also had learned that Autumn lived by herself on a small farm that had a small orchard. Every spring she would plant an extensive garden and grow many vegetables and fruits that she could enjoy fresh, and that she would preserve (usually through canning or freeze drying) her bountiful produce so that she could enjoy those foods through the fall and winter, and into the next spring. And, she did collect edible products from the forest to augment her food supply and provide medicinal products.

I had been in my community a little over two years, when I was surprised to see Autumn’s name on my schedule. I knew that she wasn’t a proponent of “Western” medical care, and that made me more curious about the reason for her visit.

When we first met, in person, at that clinic visit, I believe that Autumn was about 53 years old. I introduced myself and shared that I already knew a bit about her, and how some of my patients really loved and appreciated her. And, I did ask about the reason for her visit (she hadn’t given a reason when making the appointment). She shared that she had heard good things about me, too, but she wasn’t going to come and see me until she felt fairly certain that I would be staying in this community. I reassured her that I was very happy here and had no plans to leave. She told me that she just wanted a basic check-up. She stated that she had gone through menopause the past year, and wanted to be sure that everything was okay. We did a general physical exam, including a breast and pelvic exam, along with a PAP smear (we didn’t have HPV testing in those days). I discussed with her the value of getting a screening mammogram and screening sigmoidoscopy (yes that is what we did before colonoscopy) given her age, but she declined those tests. She was willing to have some basic lab work.

Autumn was a vibrant and energetic 53 year old and her exam and lab tests were all normal. Neither she nor I were surprised by that. I did recommend that she return for annual exams (that is what we did in those days), and she did agree with that. She did invite me to join one of her nature walks, but they were always during the day on weekdays when I was in clinic. I regret that I was never was able to take advantage of that special opportunity.

Autumn faithfully returned for her check-ups the next three years, and every visit was the same. She was the healthiest 50+ year old that I knew. Every year I would offer her screening mammography and screening sigmoidoscopy, and she would politely decline. I enjoyed those visits as opportunities to get to know her better, and learn a little about the local herbs that she would collect for medicinal purposes. It helps to know what your patients are using besides what you recommend or prescribe.

Four years later, when Autumn, now 57 years old, came in for her annual exam, she actually had a complaint. She said that she was feeling great, but she had discovered a small, hard lump in her left breast. Everything on her exam and her lab work was normal, EXCEPT for the 1 centimeter diameter, hard, fixed lump in the upper outer quadrant of her left breast. There were no overlying skin changes and I could not feel any enlarged lymph nodes in her axilla (her armpit). I shared my concern that this could be an early cancer, and that I wanted to refer her for a mammogram and surgical consultation and likely a biopsy. Autumn thanked me for confirming her suspicions and stated that she did not want to do those things. Instead, she was going to use some herbal remedies, both topical and oral.

The next year, age 58, Autumn returned for her annual exam. I was saddened, but not surprised, to learn that her breast lump had not responded to her treatments and was now much bigger. She had also lost weight and complained of decreased energy and endurance. She could no longer work in her garden or conduct herb walks in the forest. Her neighbors were caring for her farm and helping her at home. On physical exam, she had lost 15 pounds since the prior visit. Her breast mass was now about 6 centimeters in diameter, very hard, and clearly fixed to underlying tissue (it was immobile). There were no overlying skin changes, but I could easily feel an enlarged, hard lymph node in her left axilla. I did not find any other enlarged lymph nodes and her liver was not enlarged. Once again, I recommended referral for a mammogram and surgical consultation (inside I was pleading for her to get these done). But, she remained consistent in her desire to avoid medical interventions.

Her next visit was only two months later because her breast lump was now eroding through the skin of her breast resulting in a foul smelling infection in that area. She had lost another 10 pounds and was looking very thin, almost gaunt; truly a walking shadow of the person that I had known in the past. She now had multiple enlarged lymph nodes in her axilla and above her clavicle (collar bone). For the first time, Autumn was asking me for medical assistance. She specifically wanted something to treat the skin infection, something to help with the pain she was having, and something to help her with the persistent nausea that prevented her from eating well. In today’s medical environment, Autumn would have been a candidate for hospice care; either at her own home, or in a care center. But, that wasn’t available in the early 1980’s in my rural area. Fortunately, there was a visiting nursing service in a larger community that was 20 miles away. They could arrange for home health care with an aide and twice weekly nursing visits. So, that is what we ordered. And, yes, I did prescribe topical treatments for the open wound on her breast, and prescriptions for her pain and nausea.

Sadly, yet predictably, Autumn’s health continued to rapidly decline. Over the next two months I would receive weekly reports from the visiting nursing service, and I was able to make a couple of house calls (yes, back then we did that for certain patients). The house calls allowed me to see Autumn in her own environment and meet the wonderful neighbors who were caring for her and her garden. Usually, these visits were needed to discuss changes in pain medication, or possibly other medical needs.

About a week after my last home visit with Autumn, our clinic received a phone call that I had been dreading for some time. One of her neighbors felt that I needed to see Autumn that day. She didn’t give a more specific reason, but pleaded with my receptionist to have me make another home. visit. I agreed to this request for a visit, but I would need to finish seeing those patients who were already scheduled to be seen in clinic that day. That was agreeable with the neighbor.

It was probably close to 6 pm when I had finished in clinic and got in my car to make the 3 mile drive out to Autumn’s farm. I was asking myself what could possibly be the reason for this urgent visit? I had just seen her a week ago, and I had not received any concerning news from the visiting nursing service. In the back of my mind, I started hearing an old phrase: there is nothing more that you can do!

This was becoming the longest 3-mile drive I had ever taken. The road took me through a beautiful, forested area that I had seen before, yet now barely noticed. In the dim evening light, I pulled into her property and parked my car in front of her small home (more like a cabin). As I got out of my car, I could see her beautiful garden and orchard alongside the house, and her neighbors beckoning me to come in.

I entered into her darkened living room where only a few candles were burning. There was a strong scent of some herbal incense in the air. Autumn was lying on her sofa, covered with blankets because she was easily chilled. I was motioned over to a chair that was placed near her head. As I was going to the chair, I could see her face. At that moment I remembered the strong and vibrant woman from our first meeting, and now I could only see a frail remnant of that beautiful person.

My heart was pounding and I felt uncomfortable because I didn’t know what to do. After all, there was nothing more to do. Those words kept repeating through my mind. I wanted to speak; but I didn’t really want to say those words (the phrase).

I sat down in the designated chair (my chair near her head), and I prepared to speak. Before I could open my mouth and try to get some words to come out, Autumn opened her eyes, looked at me, and held out her hand to me. I remember thinking that her eyes still had the same sparkle of life as when we first met, and they brought a strange beauty to that thin, pale face. Then, she spoke first. She said the words that continue to burn in my heart to this day. “Dr. Babitz, will you please hold my hand?”

I was stunned, but didn’t hesitate a second to reach out and take her hand. I sat there, holding hands with her for a few minutes, maybe 10 (I was not keeping time). We kept looking into each other’s eyes in a silent communication. I can tell you that those minutes were feeling like an eternity. In my mind I wondered if this is what prophets see when looking into the eyes of G_d.

Then, she let go of my hand, and in a soft and very tired voice, said, “thank you for coming to see me.”

I left her home with my eyes filling with tears. I had not wanted her or her neighbors to see me crying. My eyes stayed wet throughout that evening’s drive home. I was emotionally shaken and could not yet appreciate the power of the lesson that I had just been taught. Autumn passed away two days later.

Since caring for Autumn, I made a promise to myself. I will never use the phrase there is nothing more that I can do for you. Autumn taught that there is always something more.

In later years, this lesson finally came into focus. First, when I heard the phrase, “patients don’t care how much you know, until they know how much you care.” Then, I developed my own phrase that I could share with colleagues, or health professions students or medical residents; “you can pretend to know, you can pretend to care, but you cannot pretend to BE THERE.”

If that’s all there is, my friends

Funeral dinner at the Elks Lodge, Blackfoot, ID. Self-portrait,

Digital photograph, iPhone filter, 2021

On two separate occasions, an ambulance whisked my wife’s sister from Blackfoot, Idaho to the University of Utah Hospital in Salt Lake City, Utah. About a four-hour round trip, if you speed at 85-90 mph. The second trip confirmed what most had been expecting after the first, “…there wasn’t anything more they could do for her.”

The end still came suddenly. A few weeks was the prediction, but after three days of palliative care, she passed away overnight in her house where three generations of children called it their home.

After the funeral, we head towards the Elks Lodge for her final reception held in her honor. She and her husband were club members for as long as I have known them, going back to 1996.

In 2005, you could see by his pallor, drained of all color, that his time was not long. He needed a heart transplant. A degenerative heart disease killed the father in his late thirties and the fate train was not stopping for the son to get off.

When I saw him next, he was practically jumping around. I jokingly asked if he was not part of the control group and got a monkey’s heart instead. The transplant extended his life a few more years, but with complications. Many of them arise between trade-offs of opposing forces. Eventually an inoperable brain tumor, the result of immunosuppressive drugs preventing his cells from devouring the foreign organ, hollowed out the part we knew as him and left a void in our hearts.

To go through his excruciating ordeal is like the myth of Sisyphus, punished to endless toil for cheating death. Was the punishment befitting the crime? He was a man of few words.

Even as the centrifugal forces gained strength to unravel and disperse him, he beamed like a pulsar, the remnant of a once mighty star, whenever any people he loved orbited into his field of vision.

I never felt he regretted his decision. What little extra time he would get was his, and the rest given to medical science.

Prior to his heart transplant, the hospital where the surgery took place provided housing for out-of-town recipients. At the time, one of the facilities was located at the mouth of Little Cottonwood Canyon near Sandy, Utah. The first time my wife and I drove there to pick him up and ferry him to an appointment, our mouths dropped. This facility was a compound with four identical, large, nondescript rectangular houses with a 6 feet tall or taller opaque fence encircling the complex.

When he steps out of the house, he motions us to come up. By our dumbfounded look, he says, “It’s what you think it is.” It turns out; the former property owners were polygamist, but not just any polygamists. The property owners were the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (FLDS) led at the time by Warren Jeff, who is now serving a sentence of life plus 20 years in a Texas prison for sexual assault of a minor.

The no-nonsense house is functionally organized with the largest space reserved for the kitchen. As you go through each building, just like the outside, you discover they are identical inside and disappointing. I guess I was expecting weirder. However, revulsion sets in once I comprehend, these are not so much about homes and families (bigger and merrier), but human husbandry — Monday is barn 1, Tuesday is barn 2, and so on. Dehumanizing individuals as cattle, life perverted.

We gather at the Elks Lodge down in the multi-purpose hall. It appears, on this occasion, management allowed sunlight onto the premises. However, decades of smoke, sweat, and booze deposited on the rug rise up like specters of human folly to haunt your nostrils. Weirdly, the place maintains a timeless 1970-80s “Deer Hunter” movie-like excuse for a private bar. It is a gentleman’s club for the non-land gentry type, where muscles pay for the booze and sweat leaves a tip.

I am standing in front of a makeshift photo booth. It is a simulated wood-siding panel, painted white with plastic flowers stapled to it and draped over the top as if it was a Kentucky Derby winner. Not pushed far enough into the corner to be out of the way, I am unsure if built specifically for this occasion or a holdover from a dance night. I hardly see anyone stopping in front of it, let alone give it much of a glance. I quickly take several photos until I arrive at one I do not look like I have a triple chin, and nonchalantly continue the circuit between the food and bar.

I am not one to take many selfies. I am not sure why I did, except maybe on the off chance, one of her daughters involved with the funeral planning would ask, in a group text, if anyone had taken a photo with the “garland of roses” and if so, would they send them a copy.

After midnight, my wife and I head back to Salt Lake City. The night sky is starless and moonless, no other streetlights around, and few, if any, cars on the road. It is disorienting, and slightly stressful. Even with our truck’s high-beam headlights on, you are never sure if wildlife will suddenly jump out into the road.

In the mid-nineties, I visited Spiral Jetty, a famous 1970 land-art by Robert Smithson on the edge of the Great Salt Lake. At sunset, driving back on a dusty dirt trail knifing across an otherwise uninterrupted field of Utah wild sunflowers, jackrabbits would randomly poke their head up near the side of the road and dash madly across in front of the car.

Instead of continuing, they dart and scamper up the trail, and they either turned off to the same side or not. I panic and attempt to avoid them. However, their unpredictable frequency and the risk of ditching the car in the middle of nowhere, I decided to keep straight and did not look back in the rearview mirror. The suicide jackrabbits are locally well known.

My wife begins retelling something my sister-in-law shared with her. Her sister believed she would outlive my wife despite her own frail health.

Her sister started out as a farmer’s daughter when chemical farming was the rage and dust storms were nothing but a little kick up. At seventeen, she was pregnant and a farmer’s wife. In the late 1970s, big agribusiness and banking loan practices swarmed like locusts and decimated the smaller and financially fragile farming communities. She and her husband lost their third-generation farm.

He would land a job with the University of Idaho managing the research potato fields. Free from the burdens of the annual loan repayments for seed and equipment purchase, the reduced stress extended his life. She eventually worked, until her retirement, at a Simplot plant manufacturing fertilizer and fire retardant. I remember her laugh always cut short, hijacked by a racking cough.

My sister-in-law formed this life expectancy opinion because my wife has cancer. Diagnosed in April 2015, she underwent eight weeks of chemotherapy, a mastectomy including thirteen lymph nodes removal followed by six weeks of radiation. The aggressive treatment left the scars of an all-out war permanently written across her battle bruised body.

In October 2019, the cancer returned from its hiatus and ended up slumming outside of her ureter near her left kidney. Initially, the oncologist team thought, possibly bladder cancer. The breast cancer was double positive (estrogen/progesterone) and this was double negative and signet ring shaped.

She escaped any lasting harm to her kidney, and spared a bladder removal thereby avoiding permanent bilateral nephrostomy tubes and bags. After her principal oncologist successfully argued on her behalf to the insurance company to approve the immunotherapy treatment, it ended early due to an adverse liver reaction. She has been on an oral pill.

Recently, the cancer marker is rising, and the mass inside is growing despite the increased chemo dosage. She has escaped much of the side effects, but with the higher dosage, they are unmistakable. She is easily fatigued and constantly wheezing with shortness of breath. She is in bed nearly 24 hours a day. She starts an IV drip alternative in a few days. I am relieved for the change despite the unknowns.

Before the treatment change, I plotted the cancer marker growth rate. If allowed to progress, it will surpass the previous cancer number in seven years. I am not expecting the growth rate to stay well behaved.

My wife occasionally quips a line from comedian George Carlin. I paraphrase. “I don’t know why they call it premature death. No one really knows when someone is going to die, so how can it be premature?”

She informed me, death holds no fear for her. She will decide the cost of living.

Unexpectedly, she starts singing.

Is that all there is

Is that all there is

If that’s all there is, my friends

Then let’s keep dancing

Let’s break out the booze and have a ball

If that’s all there is

Is That All There Is? – Peggy Lee, 1969

The self-made lighted disco dance floor with music synchronized

LED at The District 2017. Digital photograph, iPhone filter, 2022

AFTERWORD

I worked the summer of 1994 as a scenic artist transforming a western town to look more Hollywood western for a TV period movie. Film production comes to Utah, if not for the scenery, then for the cheap labor of non-union workers. Working 6-day weeks for 12-14 hours a day are the privileges granted by our right-to-work state. The grind was not all dust and nails. As a transplant to Utah, the commute between Park City and Morgan was postcard-like for someone who had not yet seen ‘real’ scenery.

The production goes crazy in July with a week left until filming starts with the set half built. Before High Definition (HD) TV, the scenic work is only a facade as the background is usually out-of-focus. Two days before the film crew arrives, everyone works thirty-six hours, sleep eight, and work another sixteen.

Our crew chief quits the project, placing my employment in question. My crew friend insists we drive to Park City so he can pick up his paycheck. The stretch of highway between Morgan and Park City was lonesome and with July’s scorching heat plus little sleep, it is inevitable, we would both nod off only a mile to the exit speeding close to 90 mph.

I was startled awake from metal hitting metal. I ask who hit us, and I hear, “Oh shit!” repeatedly. We hit another car and went off the road. Miraculously there were no road signs, no guardrails, no fence posts and no ditches to do horrific damage.

We check on the other driver. He is a little shaken up, but none worse for the wear. He says when he looked in his rearview mirror; he thought to himself, “They are going awfully fast.” Before he could react, we hit.

It so happens, going 90 mph for us but 75 for him, the impact speed is only 15 mph. The high-speed bump slowed our vehicle from catapulting into the field. The production company refused to cover the accident as it was off the clock. Two weeks of pay evaporated like sweat drops on a scorching asphalt from towing fees between Park City to Salt Lake City, and the repairs.

I receive an invite to the “End of the Production Wrap Party” in September to be held in Park City. There will be a live band, food and an open bar. I show up determined to make up for my friend’s pay loss.

At the bar, my wife’s friend introduces us. The band was so loud I did not say much. She loves to dance, easily attracting attention around her. I had drunk sufficiently to overcome my shyness and joined her dancing group. I might have smiled a little. After the band’s final encore, we exited together and gathered with the other drunkards milling about just outside.

The remaining heat rising off the street warms our group as we ping pong down Main. I happened to look up, and marvel. The mountain air was so clear I thought I had telescoping eyes. The Milky Way majestically unfurled with breathtaking clarity. I felt cosmic kinship to my primordial ancestors.

After a year of dating, we moved in together. I was freelancing while booting up an art career, and so worked from home. As a “house husband”, I was in charge of two cats, Miles and Shadow, and her daughter, 4 years old. Miles would die from kidney disease, and we harbored guilt believing our indecisiveness caused him needless suffering.

Like his namesake, Shadow was a constant companion. He loved greeting and giving generous affection to everyone. He changed my opinions of cats and I learned invaluable lessons about unconditional love. When old age immobilized him, I feared what his absence would sunder.

I fiercely held tight. A 3-night stay at the veterinarians, then at home, injecting water under his skin 5 times a day, while hand feeding what little he would eat. Later, I would be furious at the veterinarian office for one, pressuring me to have “emergency” care for a blind and immobile 17-year-old cat, and two not counseling about unreasonable expectations for favorable outcomes

after the care.

At the time, that was far from my mind. I retreated to my wife’s place with Shadow. I stayed every day and repositioned him following the sun throughout the house. He knew every spot, as he loved the heat. So much so, he could sleep within a foot of the gas furnace flames.

One morning while drinking my coffee, I look over at him when he makes an effort to rise. I picked him up, and brought him over onto my lap. I gently comforted him. I delayed going back to work for as long as I could. Eventually, I nestled him in his bed over the radiator, said I would be back and closed the door behind me. When my wife got home, she called to say he had

passed away.

During this period, my wife and I were living separately. We did not seem to want the same things and our life stalled. She asked if I was unwilling or unable. I explained my blockage. Imagine we had walked across an expansive plain, and then suddenly come upon a ravine with a slackline spanning the abyss. She on the other side beckons me to her. Gripped by fear, I am unable to cross.

I took Shadow’s death hard. It flung open locked drawers of childhood emotions. I had an unhealthy mistrust of relationships from fear of abandonment. Orphaned as a baby, adopted at 5 years-old and my adoptive parents separated two years later.

Three years would pass before I could think about another cat. In the interim, under the aegis of my wife’s limitless love, I undertook healing journeys for my early trauma, classes for personal responsibility, and read the book Iron John by Robert Bly. His insights about male development in the absence of male role models resonated with me. My tool bag was missing much.

My wife and I reunited and we bought a house. Our family moved in. She insisted that my stepdaughter and I adopt two kittens from the rescue shelter.

They were magical. I discovered I could love them just as intensely, and have room for more. I would experience the heartache of loss again, as each would pass away, one hit by a car and the other never found. She would insist we adopt again.

I return to the present. Surrounded by our two recent additions Queen Diane and Duke Dragon to our Kingdom of the Noble Cats of Stroudd Land. In between the chemo changeover, the side effects have subsided and she is unencumbered by pain. We all watch spellbound by her dancing. My wife is a joie de vivre, lifting my furrowed brow of worry.

Wake me up before you go-go

‘Cause I’m not planning on going solo

Wake me up before you go-go (ah)

Take me dancing tonight

I wanna hit that high (yeah, yeah)

Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go – Wham, George Michael, 1984

Shadow 2003, King of the Noble Cats of Stroudd Land. Digital photograph, iPhone filter, 2022

Colophon

I am not a god

who can stare into your soul

I am not a priest

in a wood confessional

my job is to help

and I’ll be here by your side

try to understand

as I pry out points you hide

still your life is yours

with your friends and loves to quote

I sit here with you

but

I’m an end-of-life footnote

prior to collapse

Abandoned, but never forgotten

Love Heals

The Hearth

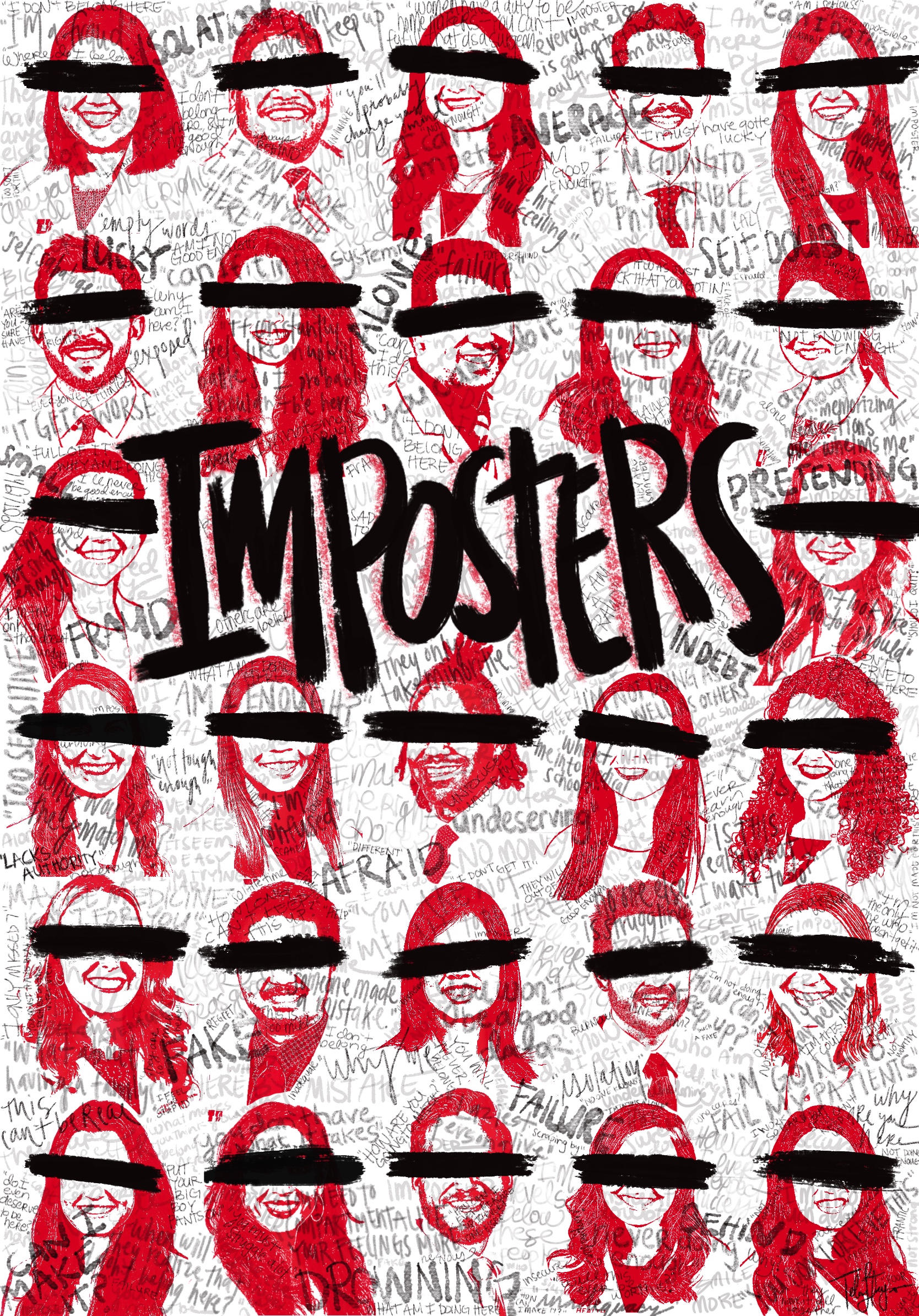

Imposters

Treatment odyssey

The Last Lullaby

How are you doing,

Mentally,

Caring for COVID patients?

The response in my head,

A letter,

Never read:

Mr. L,

I didn’t want to learn the dosages of Ivermectin

Outside of intended use.

Your telehealth provider makes me see red.

Your ventilator amplified

The Last Lullaby.

You loved many.

They watch over you.

Extubated.

Cold.

Bald Eagles and Chemo

I knew it was coming.

After my morning walk, I sat down and ran my fingers through my hair—and ended up with a handful. Right on schedule, Day 14 following my first chemo treatment for stage lll inflammatory breast cancer.

Taking what remained of my shoulder-length hair and cutting off what I could with a pair of scissors, I noticed how much I looked like my dad, now that my features, rather than my hair, took center stage. Then my husband shaved off what remained as I sat on an overturned Home Depot bucket in our backyard.

While shaving my head, my husband said, “Now you know how I felt when my dad cut my hair as a boy, coming at me with all seven of his attachments.” The kids used to call him “Bald Eagle” after he got one of his dad-inflicted haircuts. This went on for years until his mother cried one day and begged his dad to let her take him to a real barber. So, it helped to laugh as my hair fell to the grass.

Although I was pleasantly surprised with my head shape—very symmetrical, no bumps or dents—I was surprised, for days, each time I saw my bald self in the mirror. I didn’t shed any tears; in some ways it was a relief to have something I’d dreaded just happen and be over with. But my tentative confidence in my new look didn’t extend beyond the walls of my home, so I filled a rack with silk scarves and straw hats to wear each time I ventured out into the world.

This morning, many months later, I woke to an unusual sight out my bedroom window. Perched at the top of a very old tree, on branches that were almost dead-looking, sat a large brown bird, much larger than the robins and crows that typically nest nearby. As I squinted to get a better look, I noticed its majestic whitehead surveying the yard below—a bald eagle!

Somehow, I thought they lived only at the zoo, but here was one, a few hundred yards away, in all its regal splendor. Mesmerized, I watched for ten full minutes until it gracefully spread its wings and continued its journey.

I guess it’s not such a bad thing to be bald.

Ode to Outpatient Shadowing at the Children’s Hospital

After Kevin Young

Praise to animals doodled on intake forms

Praise to the rattle of pretzels in Tupperware

Praise to stools that spin

And to the children that spin them

And to walls for launching from

Praise to headbands with red bows

Civilizing the snarl of unbrushed hair

Praise to green trucks that wind up

Praise to orange onesies

The exact shade of a creamsicle

On a hot summer day

Praise to the mother with a list of questions on her phone

Typed after cleaning up vomit

Or in the dark after bedtime

With eyes nearly closed

Praise to the father poised to catch his son

Praise to the sister who joined her baby brother

On the exam table

Rubbing his head like an eight ball

Offering up her stuffed panda

Praise to the boy who couldn’t stop talking

And the doctor who paused to listen

Praise to wiggling limbs

Praise to snot and blown noses

Praise to the crunch of exam table paper

Praise to the toddler who tore the paper into pieces

Not in anger or destruction

But to hear it tear

Because sound can be discovery

And the spill of sound sloshes the ears

Like color does the eyes

Praise to receptionists with a box of stickers

Praise to floor-length windows

That allow the sun to

Filibuster florescent light

Praise to the shaggy fur of the bear in the lobby

Labeled Ursus Arctos

Praise to no follow-up needed

In the waiting room

A person who knows no roof

But intimately knows his green tarp

A person who lost his friend

To the cold last week

A person who gives bear hugs

And likes to read

A person who has not had the chance

To wash his jacket since

It was fished out of the donation bin

This person sits in the clinic waiting room

And pulls out a baggy with

Deodorant shavings

Calming the tremor in his hands

He grabs some shavings and smears them over his jacket

And pants and neck

He’s worried he’ll offend the doctor’s nose

Glimmer

The desert sun does not shine faintly

Its light unwavers at the first glimmer of the dawn

No dim perception

A simple twinkle becomes a sparkle and then a shimmer

No feeble nor intermittent glow

Its brightness not subdued at break of day

Its luster—steady, brazen as it meets the moon

Today

recalled this shine—a yearning, an inkling of

a near forgotten dream

tucked away deeply, safely

for a moment such as this

such as now

A moment to remember

that hope

can sometimes

be a verb

I am sorry, honey

I had run the hill past the Montessori school hundreds of times

But now I couldn’t, breathless.

Then, blood in my eye, in my nose.

An exquisite April day

Under a flowering tree in the park

I told my husband they saw blasts in my blood.

Leukemia.

A turn in the course of our lives.

*First published in 2021 Voices from the Faculty

Anatomy and peace

To Crochet

I can’t pretend to understand

What it is to make something

Out of nothing but chaos and string

To use nothing but my hand

And perhaps a tool or two

To make a hat that would fit a king

And on brisk slicing sidewalks

That turn quickly to slide-walks

I wonder how long it would take to develop this skill

But with patience and money fleeting

And barely time for eating

It’s mostly desires like this that come to nil.

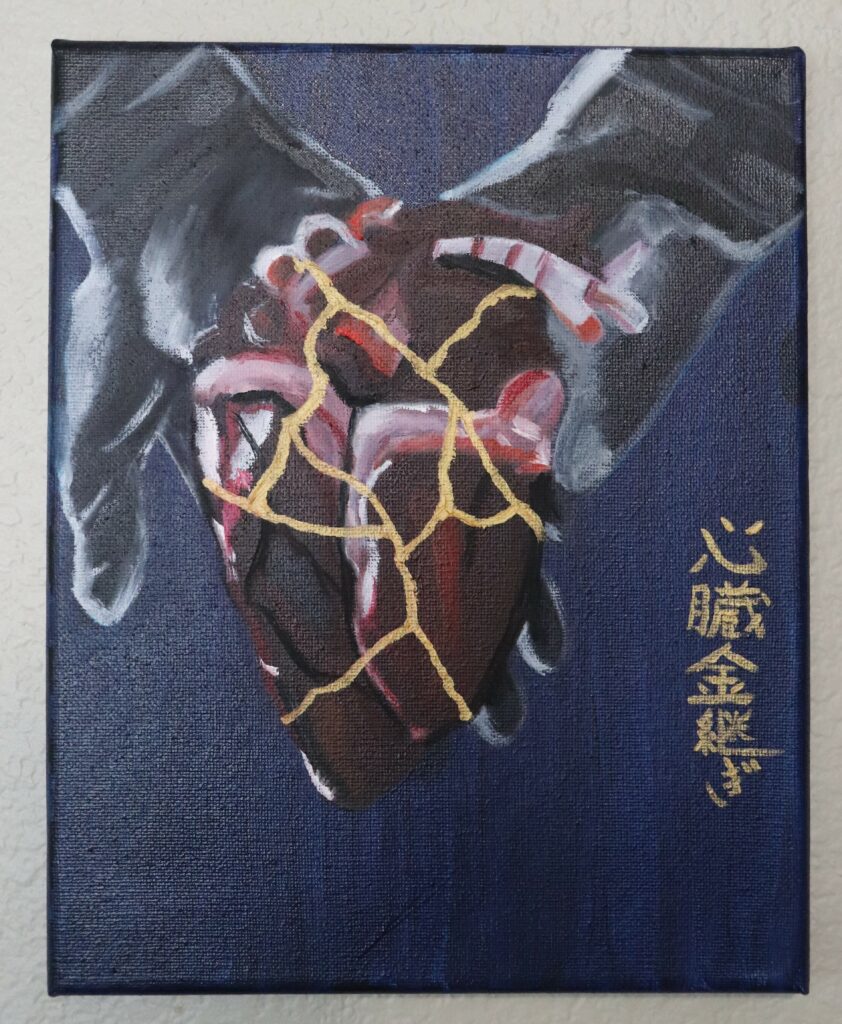

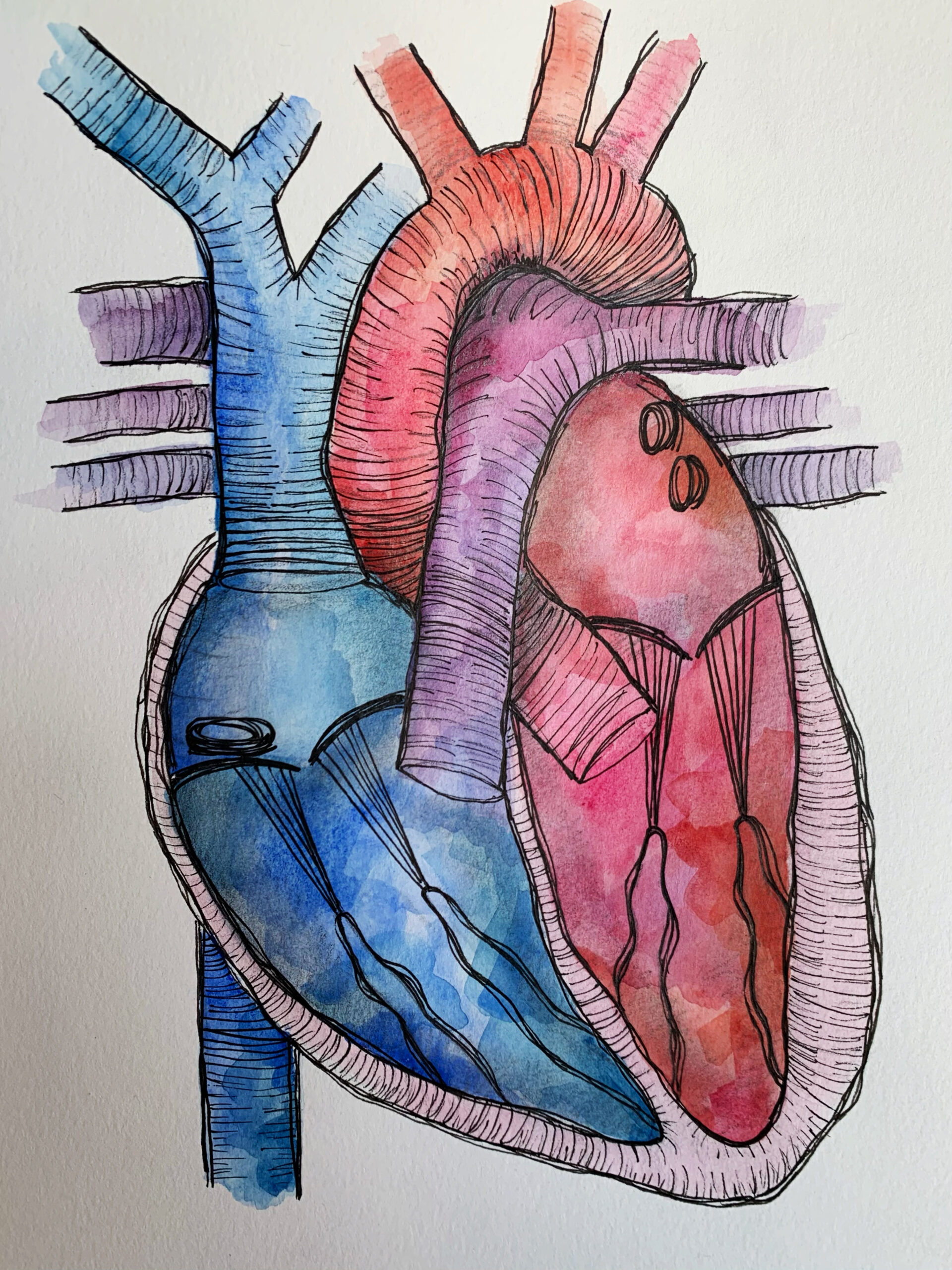

Shinzou Kintsugi-The Repair of the Heart