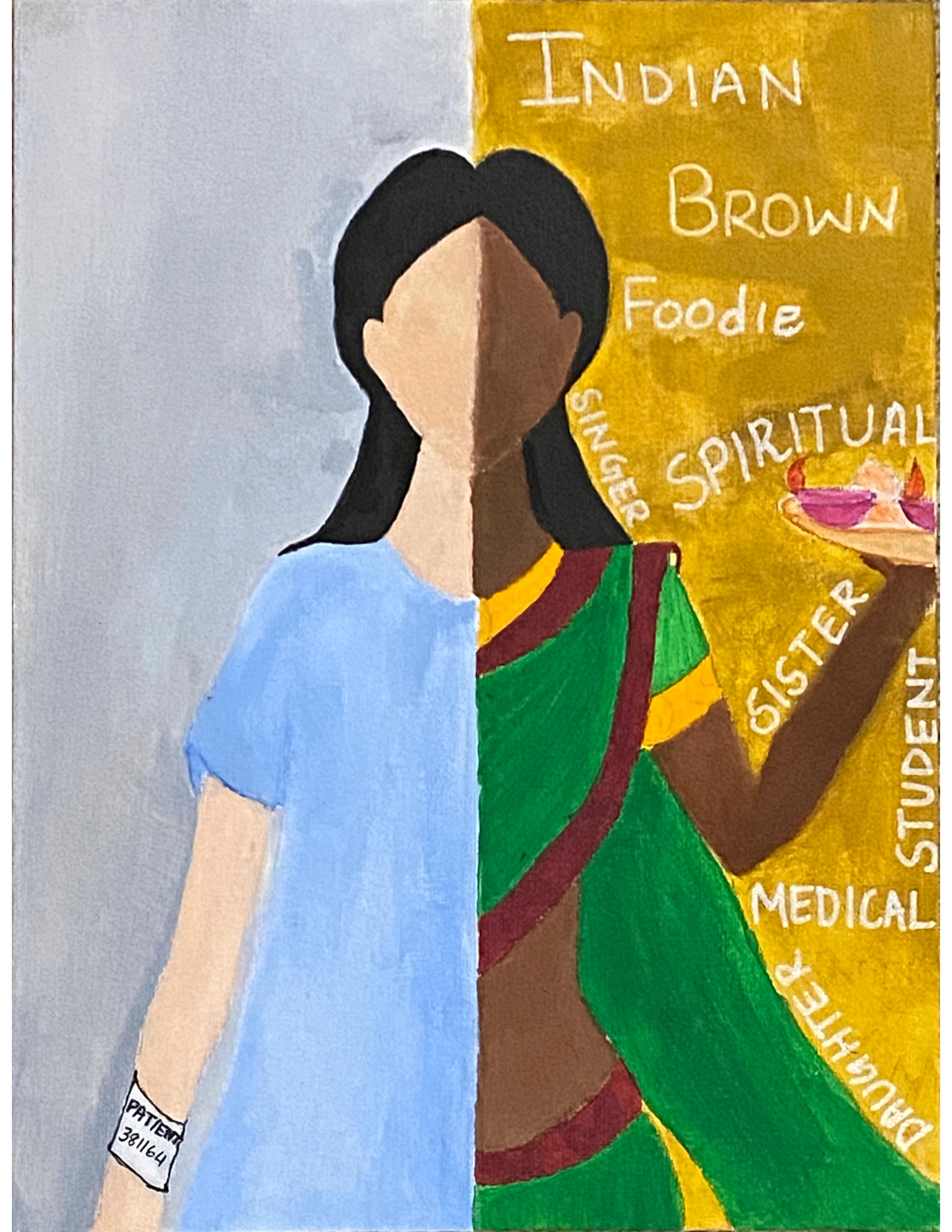

Skin

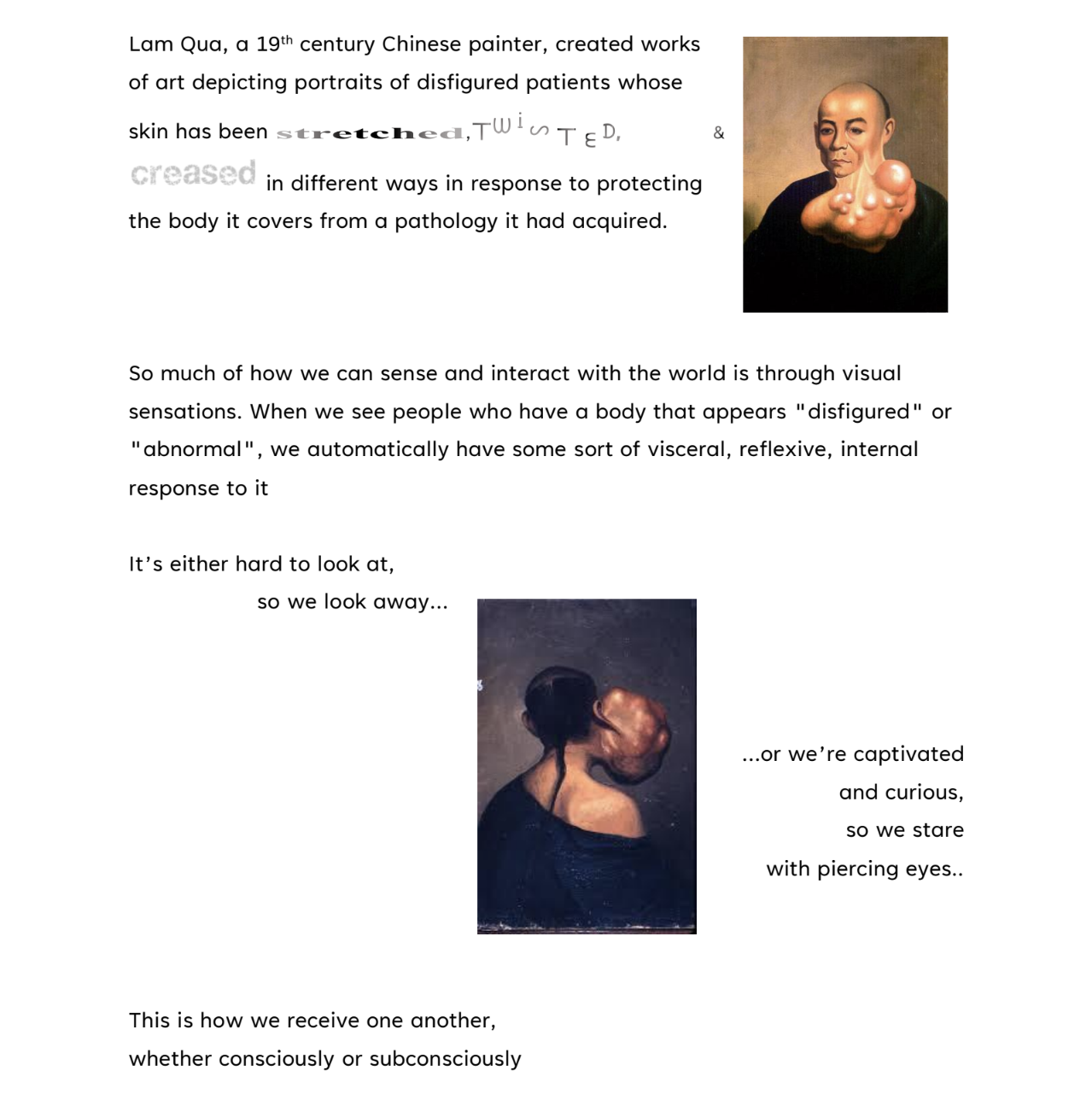

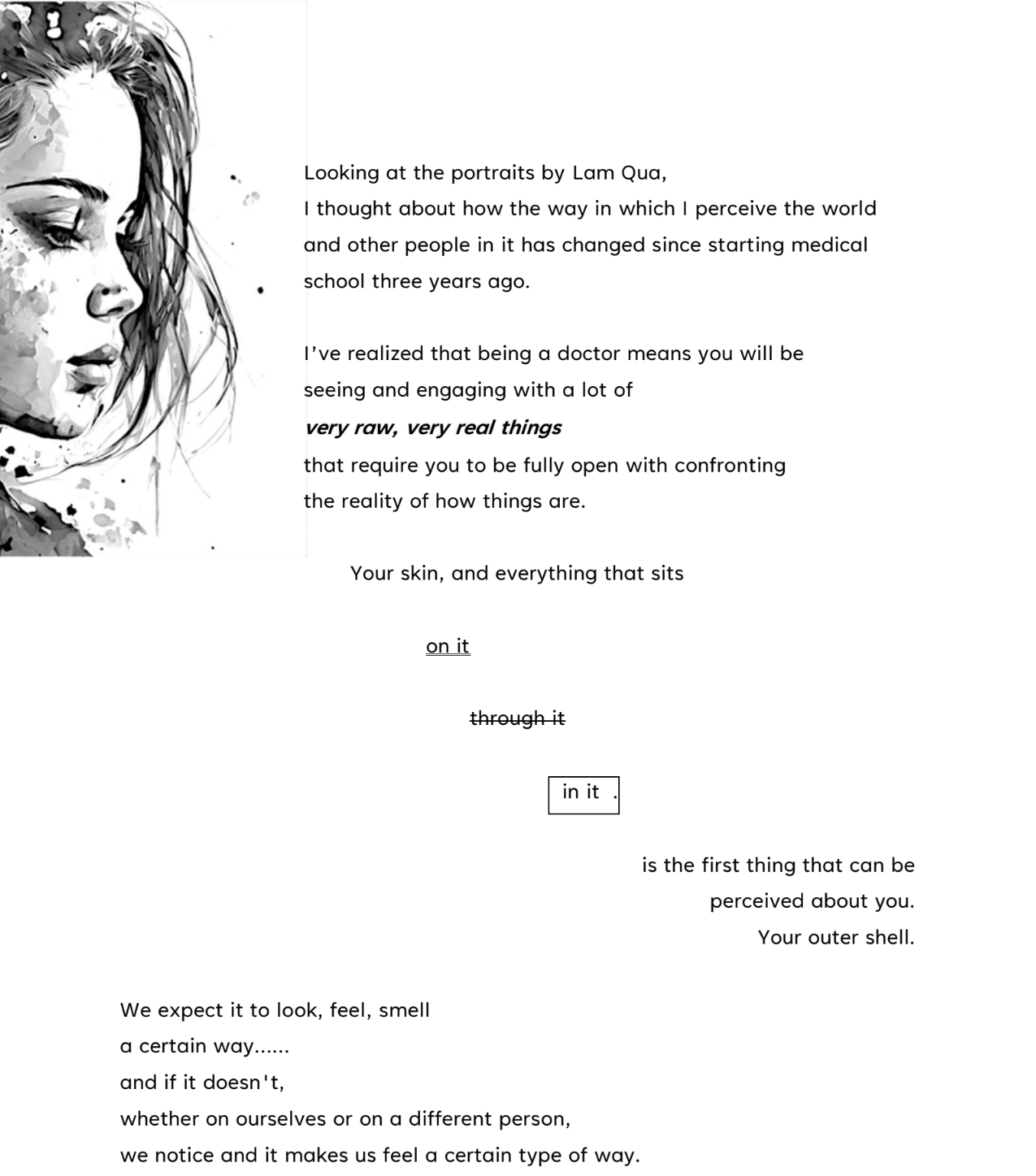

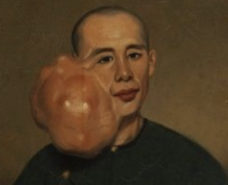

Images used by the artist include Portrait No. 40, Portrait No. 48, and Portrait No. 47 by Lam Qua. Images used courtesy of the Peter Parker Collection of the Whitney Medical Library at Yale University Library.

A Stitch in Hand

Embodied Grief

My Memory of You

In Terms Of

Stillness, Come Sit With Me

I wish in these hours of tendon, bone, salt

the erratic jump of machine’s tracing

with heart’s beat

Lub dub lub dub lub dub

I wish you could pour down the sulci

of my constant inside talk like summer rain

in the seconds before it all stops—

Leave me with the slow drip of one

last word from lilac bushes

faintly purple on the roadside

Teach me how to slow the beating

of not good enough and what if

and the more more more

Let me sit with you on the side of this lake

where the air tastes like fish

and water ripples with my toes

Watch the sailboats make their last circle

as the loons sing feathered wisdom

to the fading light

Shared History

I say, “What seems to be the problem?”

You say, “I don’t know. You called me in.”

I say, “Are you getting enough exercise?”

You say, “I’m too tired after a day on my feet. My muscles ache from

the up-down-up-down-up-down.”

I say, “Are you taking your fluoxetine as recommended?”

You say, “The little half-moons? I take a couple when I feel too down.

Regularly, just like you said.”

I say, “Do you have a support system for after the surgery?”

You say, “Yeah, my dog always helps me feel better. Don’t worry about

me, doc.”

I say, “You’ll need a radical orchiectomy.”

You say, “That’s fine, but can I keep my testicle?”

Family Medicine Rotation 8.27.22

Brachial Forest

Entangled

What’s in Your Hands?

What was in your hands when you arrived at the Emergency Department?

Your belongings that you wanted to make sure got to your hospital room

3 days later?

Your chest as we discover fluid around your heart

In the ICU?

Your husband’s wrist as your heart speeds up past normal levels

In pre-op?

Your neck as we go to surgery to take out the thyroid that got inflamed

from the medications to slow down your heart

On the floors?

Your Cincinnati Bengals Jersey, finally relieved to be out of the ICU and

watching football

A few nights later?

Your mouth, covering up a cough from the pneumonia that you caught in

the hospital

Another trip to the ICU

The next Bengals game?

The bed rail, as the wounds you’ve developed over the last month are

almost too painful to bear

Yet another week in the hospital?

My hand

It’s been a long month.

6AM/PM

What have we to show?

Walking home

Under the empty

Orange light of sodium street lamps

After even the stars have gone to bed

And the sidewalk slush soaks scrub hems.

Too tired to stuff speakers into our ears

As to avoid being left alone

With the siren-silence

And our thoughts.

Fresh footfalls indent the snow

Heading back the way we came.

Recall that those wet rubber soles squeaked

On the cold linoleum as if to punctuate

The pablum of our patient plan.

One of us has forgotten to wipe the blood

From the space between the treads.

Where is the purpose

We have lost in the place between

No particular morning or evening?

May we find it when again we meet

At the Intersection of Coming and Going

Of the lives that need ours most.

Til Death Did Us Part

There were no last breaths to take

You couldn’t

Just beats of your heart

I promised you wouldn’t be alone

I promised the kids

You weren’t

By your side I lay

You were at peace

No longer suffering

No hunger for air

Just you and I

As the saying goes

Love someone enough to set them free

You were free

Free as a bird

Freebird

Your favorite song

Our last cuddle

Til death did us part

Bayanihan

There’s a Filipino word:

bayanihan

(buy-uh-nee-hun)

which roughly translates to a spirit of helping your

community without expecting anything in return.

Bayanihan:

also the word used to describe the tradition of

neighbors coming together to move a family’s nipa

hut from one place to another.

In this way,

life is carried on the shoulders of the community.

A nipa hut, or bahay kubo, is a native Filipino house

made of wood, bamboo, and nipa grass.

In bayanihan, the bahay kubo is uprooted using

bamboo poles, hoisted onto the shoulders of 20 or

more people, and moved to a new location.

The bahay kubo being carried often also contains

the family’s belongings and even family members

incapable of making the trek.

The community moves as a single group, all vital

parts of the same journey.

All equally contributing to accomplish the goal.

Life is carried on the shoulders of the community.

I think of the practice of medicine as its own

bayanihan.

Consider the burdens, which the patient’s

shoulders alone cannot bear.

The burden of sickness, the burden of stress.

The burden of finances, the burden of emotion.

The burden of the future: not knowing, knowing too

much.

The burden of a life that did not unfold according to

plan.

These burdens that need a community’s shoulders

too.

Life is carried on the shoulders of the community.

We are the community.

Family members, loved ones, friends,

Physicians, nurses, pharmacists,

Practitioners, technicians, assistants,

Administrative teams, social workers, dieticians,

Volunteers, sanitation services, maintenance

engineers,

And countless others more who come together

because

life is carried on the shoulders of the community.

What is our role as physicians in this bayanihan?

We enter a patient’s life as one member of this

community.

Our work, our training, our struggles, our rewards

all giving us the strength to take a step forward,

difficult as it may be,

To take the patient’s bahay kubo one step further,

wherever that may lead.

Life is carried on the shoulders of the community.

We fall in line, we grip the bamboo pole, we make

the trek and shoulder the haul.

We don’t let the patient carry their bahay kubo all

on their own.

The bahay kubo that holds burdens.

The bahay kubo that holds a precious, shining, and

full life.

As my ancestors carried the lives of their neighbors

on their shoulders,

I, too, will carry the lives of my neighbors on my

shoulders.

What a privilege to be part of a bayanihan, where

life is carried on the shoulders of the community.

Salt Lake

The Elijahs who parted the waters with the rod are gone

And we remain

The chariot of fire and the whirlwind

The woven mantle and the staff with which to split the sea

Fall to us

The coal fire and the dam dynamo whirling in the spray

The white coat and the uranium control rod

But we are not prophets

We simply can see

And shout from the high places

That the machines we wrought were not miracles

That the land is barren and the rivers overrun their banks

No salt of the earth

Cast into the sea can make it clean

The cruse of oil has faltered and the measure of meal has failed

The bears are coming from the forest

The foam receding from the pebbled shore

Where stands not a host to safely cross

But a sprawl thirsting evermore

Pilfering the waters until the sickly light pierces the sediment

Where the Leviathan lies

Beneath the silt of the ancient lakebed

And roaring he ascends

Be he creature of many sinewed heads

Or clouds of Mercury, Arsenic, Lead

All the same

Those wefting limbs billow into the Valley

Piercing each palisade and cell wall

Coughing until lungs pall

And that will be all

Whether Abaddon beneath or a Hell all man’s own

You will no longer need us

A Place for Grief

It is September 19, 2022. I am one month into my first year of medical school, yet it feels like I’ve already crammed enough information in my brain to last a lifetime. Come graduation time, I will likely have lost clarity on much of the minutiae of my first year. I won’t recall how I awkwardly stumbled over my words as I practiced my first patient presentation, or how nervous I felt attaching a scalpel blade on the first day of anatomy lab. I certainly will need a refresher on the steps of the Krebs Cycle, and is cardiotoxicity a side effect of tamoxifen or trastuzumab?

However, I might remember the drive I took to class this morning. I was stopped in traffic at a red light near Primary Children’s Hospital when I heard an intense, familiar whirring sound that reverberated in my chest. I immediately turned my head to see the LifeFlight helicopter land on the roof of the pediatric Emergency Department. I felt that recognizable clench in my throat, adrenaline in my limbs, and tightness at the corners of my mouth that I always experience when I see that helicopter. Six months ago, I remember hearing that same hum of the LifeFlight’s propellers descend towards the hospital roof as I sat below in the ED social worker’s room. My shirt was stained with tears and my hands trembled. I held my siblings, William and Sarah, close. That flight was carrying our youngest brother, Henry. About half an hour prior, an Alta Ski Area police officer called to inform me that Henry had been in a serious ski accident and that I needed to get to Primary Children’s Hospital immediately. My parents were out of town, and I was needed as the responsible adult. I don’t have words to describe the pain I felt as the pediatric anesthesiologist explained that despite 90 minutes of intense resuscitation, Henry had died.

He was fourteen years old- a beautiful cellist, a talented tennis player, an adventurous mountain biker, and an exceptional student with a sweet-natured goodness about him that made him the glue of our family. Losing Henry is losing a piece of myself—my life, my identity as a sister, and my future as a medical student changed the moment he died. Sitting with Henry’s still-warm body in the trauma bay of Primary Children’s Emergency Department, I never wanted to enter a hospital again. I doubted that I would have the resilience and capacity to succeed in medical school under the weight of such immense grief.

I was in such bright spirits this morning before I saw LifeFlight land. I worked so hard to memorize the steps of muscle contraction and was feeling confident to be quizzed on it this afternoon in class. I’d done well on my assignments all week and was feeling invigorated and eager to tackle another day of learning. The instant I saw the helicopter descend, the resolve and strength that I’d enjoyed this morning immediately crumbled. I felt transported back to the social workroom, and I felt a flood of the same emotions I experienced when Henry died. I wondered if this patient’s family was also waiting with the social worker below, and I hoped more than anything that the child was okay.

I struggled to regain my composure before walking into class, flooded with self-doubt about my place in medicine. If every LifeFlight prompts such pain, can I ever be successful working in healthcare, responding effectively to trauma, emergency, and death?

It is February 20, 2023. I am now approaching the end of my first year of medical school. It has been a full year since Henry’s accident. I still feel the grief, a steady presence through each moment. Navigating tragedy in my own life has brought me in tune with the aches of those around me—classmates who have lost parents, mentors who have lost children, and neighbors who have lost loved ones. I have come to understand grief as a friend—a lifeline that fosters connection to the humanity of another person. From grief sprouts a greater empathy, compassion, and sensitivity. It connects me to Henry, too. I have felt this pain and I can now see it in others. Grief is pervasive in medicine. Loss is intrinsically intertwined with the effort to heal.

I keep a photo of Henry tucked into the back of my student ID badge—the last school photo he took. I see a bit of him in every patient I meet. I miss him profoundly. Glancing down at my lanyard throughout the day, it serves as a reminder not to harden myself against the heaviness of loss, but rather use it to fuel my sincere commitment to providing healing, connection, and comfort for those in my care. This is the place of grief in medicine.

Heavy

My Name is Not “Patient in Rm#”

Stage Four

She is stage four.

Knowing this will take her life,

Someday.

Her daughter knows too, but no one else can see the tiny cluster of cells on her liver; in her brain.

When they hear she has cancer they think it must be early because she still has her hair.

They don’t realize it’s a wig.

She just wants to see her children graduate high school,

But there’s always another milestone, always something she’ll miss.

Knowing she’ll be okay but what about everyone else she’ll leave behind?

How does she tell her kids she is dying of cancer?

She wants to show her daughter where to spread her ashes in the mountains, but she’s been feeling short of breath recently and her latest scans showed something new.

A met in her lung.

Her friends notice she’s stopped going to weekly support group meetings.

The unfortunate sisterhood; living through it together, fighting.

But, also dying.

They go to her celebration of life, but that makes it all more real.

The sisterhood continues; the rest continue living, however long they have left.

A new member walks in.

She is stage four.

Crabby

Sometimes the Shape of Grief is a Stethoscope

There is a certain bittersweetness in the place

That marks my journey to physicianship.

The place where my mind blossoms

And my heart will always ache.

It is here, in the hospital,

Where I am both the eager learner

And the bereaved family member.

The bright-eyed student,

The twin-less twin.

As I walk down the ever-teeming corridors

I see doctors bustling

And families mourning;

Myself, I find in both.

The wonders and woes of medicine

Irrevocably interwoven into the fabric of my white coat.

I see the place

Where I said goodbye to you.

My heart races

And swells,

Beats and lulls.

The symphony of sorrow

Plays on

Sometimes the shape of grief is the stethoscope

That hangs around my neck.

Familiar, so achingly familiar.

The magnitude of its weight

Only perceptible to me.

They tell us not to forget what makes us human.

That practicing medicine can make us cold.

But how could I ever brush past the sorrows of my patients

When I will never go a day without reconciling my own?

In the place that knows such profound sorrow

And such profound joy

Let grief be my greatest teacher.

In lieu of sending flowers,

Let me nurture my patients to bloom.

Malar

after wards

Rooms where there is living and dying

Giving and drying

Eyes, diagnoses either millstones or balloons

On frail necks.

In these touchstone rooms we make our house,

And forsake our spouse

At home, that home. Our promises are full of “soons”,

Our ears, “Next?”

In their beds our guests slumber evades

Cacoph’ny in spades

Sings them restless. We feel helpless, like diving loons.

We are specks.

If I could heal, I’d make us holy.

Ask Death, “More slowly,

Give us more time. More moments for larks’ lofty tunes.”

He objects.

What is Love?

Is it a gentle kiss?

Is it a whispered promise?

Is it a summer day’s bliss?

Is it relinquishing your freedom to be with them?

I saw it there, in a memory care unit

He was the only person she knew

He still understood time, place, and her heart

But couldn’t bear to part from her, and got admitted too

In sickness and in health, for better or for worse

70 years together, not a day apart

When death did call, together they traversed