A Message from the Editor, 2019 Volume 7

Dear Readers,

Thank you for picking up the 2019 edition of Rubor: Reflections on Medicine from the Wasatch Front. This year’s publication includes some powerful and thoughtful visual and literary works that explore current pressing themes related to medicine.

This past November I interviewed Dr. Rafael Campo, current poetry editor of JAMA. As an editor of Rubor and a proponent for the medical arts and humanities, his words resonated with me:

When we think about the humanities, we think about morality. We think about ethics. We think about power dynamics. Who gets to tell the story? . . . that’s the joy of this work — being people together — and by presenting myself as a fellow human. I hope that models a different way of being in medicine. We’re not just robots, we’re not just technicians, we’re not just in our white coats in disguise. We’re people. All of us.

With these thoughts in mind, I am so grateful for the opportunity to bear witness and share this collection of the seventh edition of Rubor. Dr. Campo’s words remind me of how important a humanities publication is to our medical community at the University of Utah. Whether we are students, providers, professors, patients, or family members, we are united in our humanity.

We share in the experience of making mistakes and celebrating successes, as well as lives and histories that extend far beyond the hospital campus. This amounts to different perspectives and stories worth sharing.

Many different themes present within our published work this year. Multiple authors explore memorable interactions with patients, from the arena of pediatrics in “To Astra in Clinic 6,” to end-of-life experiences in “Triplets” and “What’s Worse.” Sacrifice and the ripple effects on families of working in healthcare are beautifully conveyed in the poems “Balance” and “Who Heals the Healer?” We can chuckle together over humorous hospital moments in the cartoons of “A Joke A Day.” “Differential Diagnosis: Climate Change” speaks to the far-reaching environmental implications of the medical system, a perspective that resonates with current conservation efforts of the Utah open lands. “Snoop” is a poignant response to racist comments experienced as a student doctor in the operating room, and at a school attempting to diversify its student population. I implore you to think critically and reflect on the voices present in this publication.

I’m so grateful to the artists and authors for sharing their experiences with us. I owe incredible thanks to our 2019 team of content editors and review staff for helping us select our pieces for this publication; Dr. Susan Sample for her never-ending guidance and support; Dr. Gretchen Case for her continuous advice through the publication process; the Program in Medical Ethics and Humanities for providing the primary funding and support for this publication; Kristy Martin at Sheridan Printing; and my amazing co-editors — Lily Boettcher, Phoebe Draper and Serena Fang. Rubor has filled a vital space in my heart as a medical student these past four years and I am so grateful to everyone I have had a chance to work with. Thank you for giving me this opportunity. I will miss this more than you can imagine.

With warm wishes,

Kajsa Vlasic

Editor-in-Chief, 2018-2019

Postcard to My Dermatologist

On Being a Different Man

What does it mean to be a man?

Growing up with my mom and older sister just two doors down from my Nonna, we were “the Italian-Catholics” of our neighborhood, our home in the unlikely setting of Salt Lake City, Utah. Given these circumstances and being surrounded by a community of hyper-quintessential-go-camping every summer-rigid-gender-role-nuclear families, I found myself asking this question of manhood often. And while being raised in this world of women has always brought me immense pride, I would constantly struggle to find an answer to my seemingly simple question.

The shatter of glass has always been that sound for me, that visceral grasp, tug, and wring of cochlea that gives me a moment of sad before I snap back to the reality of a clumsy accident or drunken slip of hand. For this, I thank a man. That man who calls himself “dad,” who would throw and smash through fury and shatter, shatter as mom sobbed, shatter as my sister and I hid and plugged our ringing ears to suppress this distressed, dissonant orchestra. Is this what it means to be a man?

A boy grows up when he finds himself caring for his only parent. I was nine, numbed by a din of disbelief as mom’s “just a lump” went from mammography, to malignancy, and to curative double mastectomy in a matter of two weeks. And despite my mom—a former dietitian and lactation specialist—feeling the weight of an absence of what she felt defined her career and her womanhood, she never failed to be present for my sister and me. And when playground banter brought callous, casual remarks of having just a mom, I’d think if only you knew. Is this what it means to be a man?

It was a dark time as a third-year medical student on the Oncology service, but Dr. B brought light I will never forget. Her presence was stern, yet reasonable. Her face was encased by large lenses over drooped eyes that had seen too much, yet she retained the most moving ability to be wholly present with her patients. Her handshake was not simply a “hello,” but a caress of comradery, a statement of “I am here and here for you.” Her exam was not solely an objective maneuver, but a massaging away of the misery of malignancy. The way she used her hands, her touch to ail and hope with patients, was mesmerizing. She was a human, being fully present with another human. She was light through grim predicament. Is this what it means to be a man?

As a fourth-year medical student rotating on general medicine wards, Dr. C showed me that mindfulness and emotion—cultivating it, naming it, sitting with it—can be another of medicine’s curing prescriptions. The subjectivity of emotion discomforts physicians and trainees alike, yet Dr. C took every opportunity to embrace it. Her genuine, heartfelt finesse to addressing the suffering grounded me. “I feel like there’s so much love in this room,” she said to a family as their loved one knocked on death’s door. And I could feel this phrase, see it ripple through the water of a room slowed by sorrow, and see it bring closure and peace. I know that moment was meant for family, but that ripple passed through and changed me, too. Is this what it means to be a man?

I’m a man, a different man because of women. These women who show up and stay when others leave, who touch and humanize when others ail, who uplift and embrace emotion and grow. I’m a man because of women who gave and showed me nothing short of the world. And if I can emulate even an ounce of these women, that is a different man worth being.

Triplets

When I am dying I will breathe in triplets

Until I don’t.

I will die on the third beat

and then there will be a long rest

while a sweet-faced nurse turns off my machine

and consoles my visitors.

If my dog is there, I hope they let him curl

into the crook of my knees as I lie on my side.

Just like at home.

I hope it will comfort him,

and I hope he pulls off

a deep, mournful wail when I stop.

I suppose I may be home,

but I see myself in a hospital room

with butter yellow walls

and dust motes dancing in the air.

Rhythmic hiss of respirator,

keeping good time for a machine designed by a white guy.

I would like to avoid agonal breathing

and also shitting myself or extended choking.

These are not crowd-pleasers.

I would like to be given Soldiers’ Joy,

Sweet morphine,

so my hands will be on top of the sheets, calm.

If I can, I will sit bolt upright in the bed,

and stare at the ceiling tiles,

with an ecstatic expression on my face,

eyes wide and serene, surprised mouth, O.

Might as well give people something to talk about.

And a little hope.

I would like my dog at my funeral, please.

Silver-framed if he is not permitted in person.

He drinks in triplets, messy like last breaths,

until he doesn’t.

He will whine and pace, I think,

and he will mourn me more than some others.

A poet asked me if I had seen people die, which got me thinking about how people die in hospitals. This poem is what came out of that exchange. I began thinking how I might arrange my own death if I were conscious and hospitalized, picking and choosing from deaths I had seen. I once had a lovely Newfoundland with impeccable manners (she would “lie down” but not “lay down,” to one dog sitter’s surprise), whose only piece of gaucherie was that she drank water in triplets, slurping loudly and leaving half of it on the floor. Death in hospitals reminds me of that—as refined as you’re motivated to be, the structure of the place elicits crude and rude behavior.

Holes

as in the tatted walls of Canyon de Chelly

exhaling and, perhaps, inhaling

there must be some, like flutes

angling just so, that multiply the desert wind

the music Laotze said

might not seem perfect

uttering 10,000 things

just so you left one

with the void you created

vanishing slowly from the solid world

the many kind of vanishings

how I listened for your laughter

or anything particular

thus

suddenly hearing it aloud!

I remember how the painted wall of sand made stone like flesh

was seen as if sipping into those rows of mouths

just so the portions of my own breaths

draw into the apertures

for the hearts of notes —

countless types of silence, jellyfish in sound —

extend into both listener and singer

both singer and singer

both listener and listener

what holds the flutters of particles together

but the lives of uncountable spaces

everywhere flowing through

My beloved spouse died of an accidental self-overdose of methadone, prescribed for the palliation of fibromyalgia pain, possibly because of confusion induced by other normatively prescribed opioid drugs accompanying that prescription. In these times in which opioids are rightly under scrutiny, I hope that nevertheless we all will remember that for extreme pain, sometimes such drugs enable sufferers from such maladies as fibromyalgia and other forms of “invisible injury” to continue to live mobile and productive lives — and to demand wise and humane compromises that take this factor into consideration.

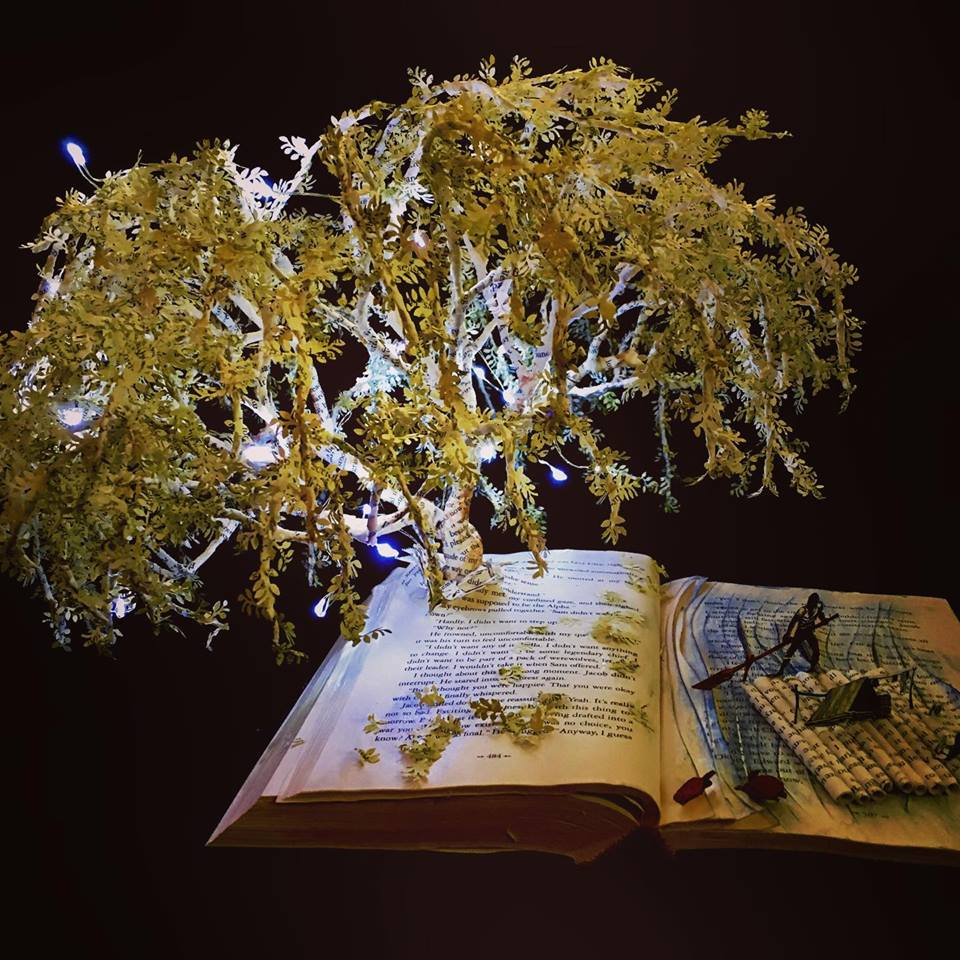

Tree of Hippocrates

Throughout my time so far in medical school, I have experienced a wide variety of thoughts, feelings, and emotions, many wonderful, some not so much. I have labored to learn many difficult concepts, and I’ve been grateful to grasp the rare simple ones without too much difficulty. I have interacted with peers, mentors, professors, and administrators, each with a unique place in the picture and a different role to play in this ever-expanding universe of medicine. I have even been able to catch an elusive glance of life beyond medicine, when I make an effort to do so, and see that there is so much more to each of these people. There is more to a physician than the white coat and prescription pad. There is more to patients than disease. It’s easy to convince myself that I know this is true, but I find myself being struck, time and again, with this realization, especially when I have the opportunity to get to know those I interact with on a more personal level.

My portrayal of the Tree of Hippocrates, a symbol of medical teaching and learning, made of over 1,100 pieces of walnut and poplar, stacked in 74 unique layers, is intended to evoke the idea that medicine is learned, taught, and practiced in layers, and that individuality is essential in forming a truly successful team. Each piece of the artwork was individually measured, cut, placed, and glued into a specific location, and it takes them all working together to make the picture of the tree take life. Likewise, we all bring our unique talents, strengths, opinions, and goals, and only when working together in harmony can we visualize the layers and depth that transform our contributions into a work of art in medicine.

Balance

Smiling, laughter, and chuckling out of breath as two little feet rub against my beard

This is it

I am happy

Loud sounds warp me out of a memory, confusion, heavy eyes and an aching body remains in

bed

It’s still dark outside

I was happy

Scrubs on and face washed, with your hand on the doorknob you’re ready to walk out the door

I wonder if those two little feet are….

Sleeping

I’ll come home early and play with those little piggies tonight

I promise

Walk to the car, no, let’s jog.

Speed through traffic and arrive at the refiner’s fire,

Pre-round, round, present your plan and get mocked… feel shame.

Authoritative voices reiterate “study more, improve, be smarter, this is what’s most important!”

They’re wrong

Look outside and realize that time has beaten you once again,

The absence of light taunts and sneaks words into your mind

“You are late again”

Rush home and arrive at familiarity, forgiveness and love.

Walk to the front door, no, let’s run. Maybe it’s not too late.

Lights are out,

I wonder if… little feet?

Sleeping

Somewhere in between wishes and memories I’ll still play with you tonight,

I promise

Mourning’s Glory

Will you rain for me? Will you cry the

fertile tears of heaven, as I weep less

fruitful ones.

Will you show me love in your

sorrow.

Teach me growth in the times that

storm.

Give me reassurance as the weaker

parts of me are washed away.

Team 1

A composite of a dozen of my patients from my inpatient wards medicine team.

Please note that these portraits are just that, a composite. They do not represent or convey the identity of any particular person. They merely represent the most important body of people—our patients—in medicine, and the inherent associated responsibility of taking care of them.

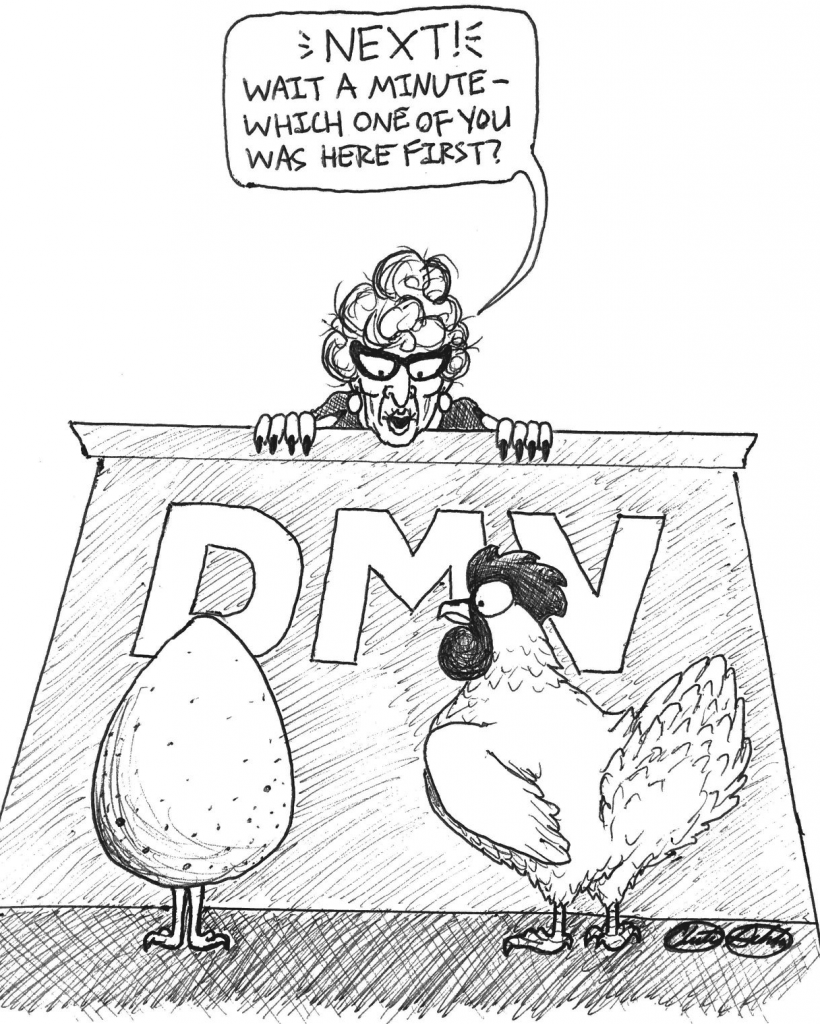

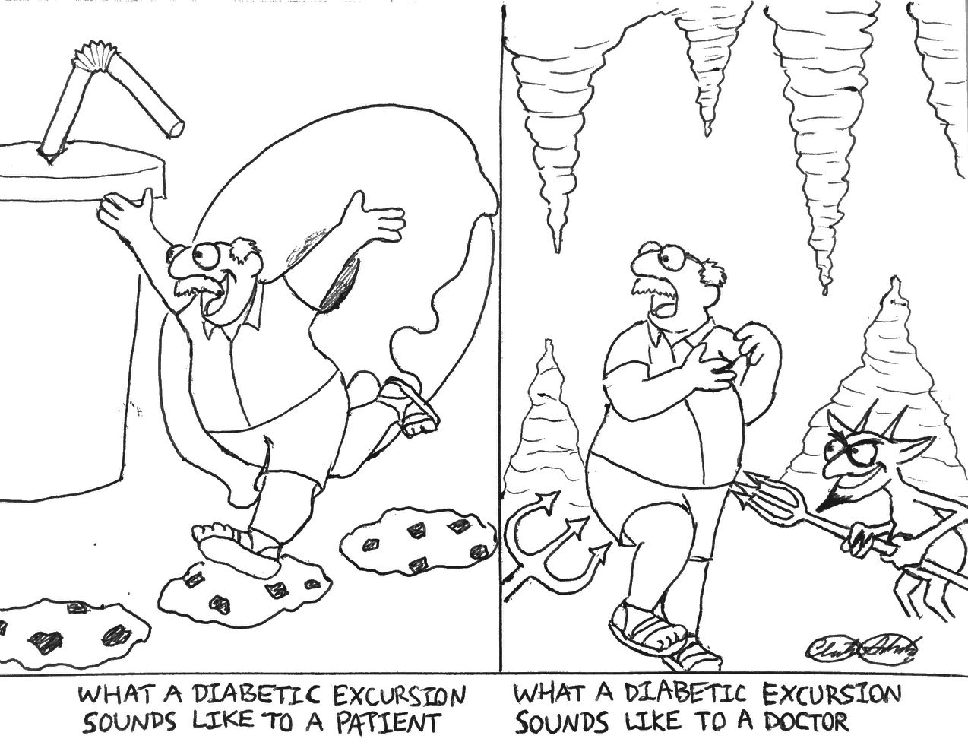

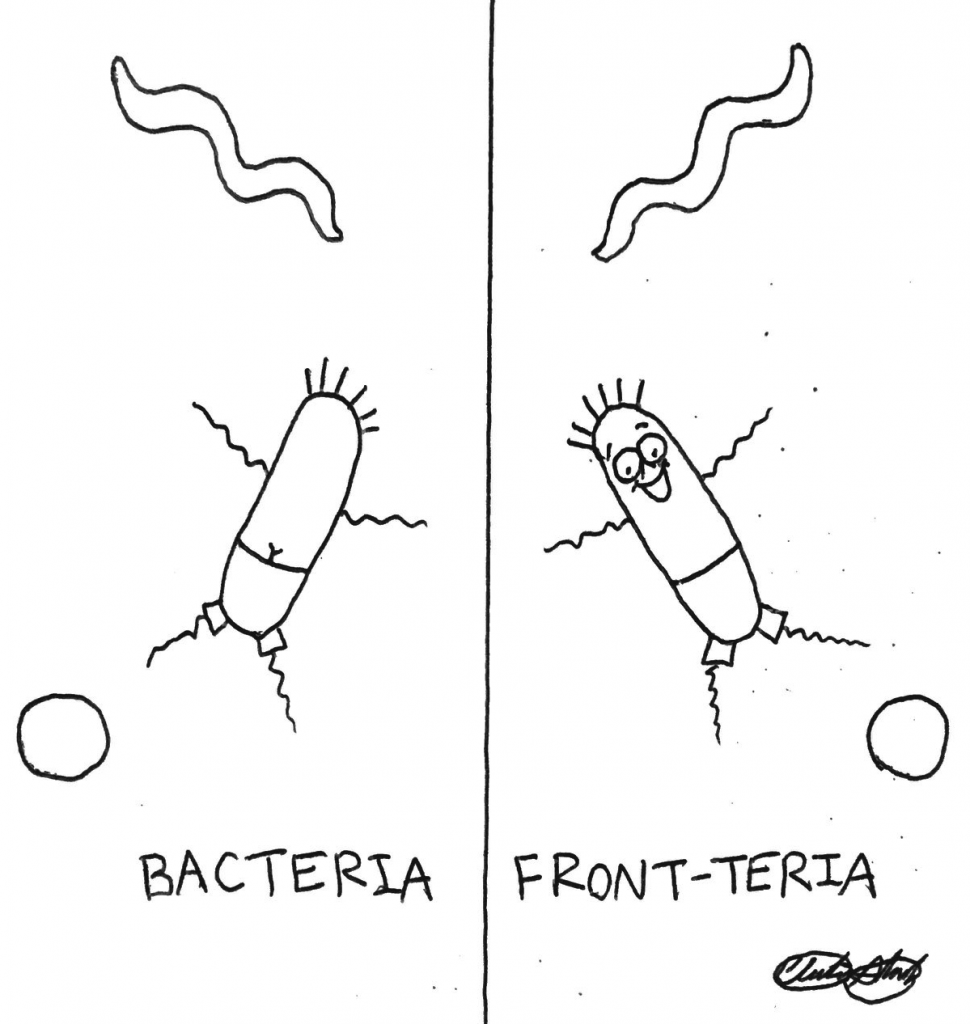

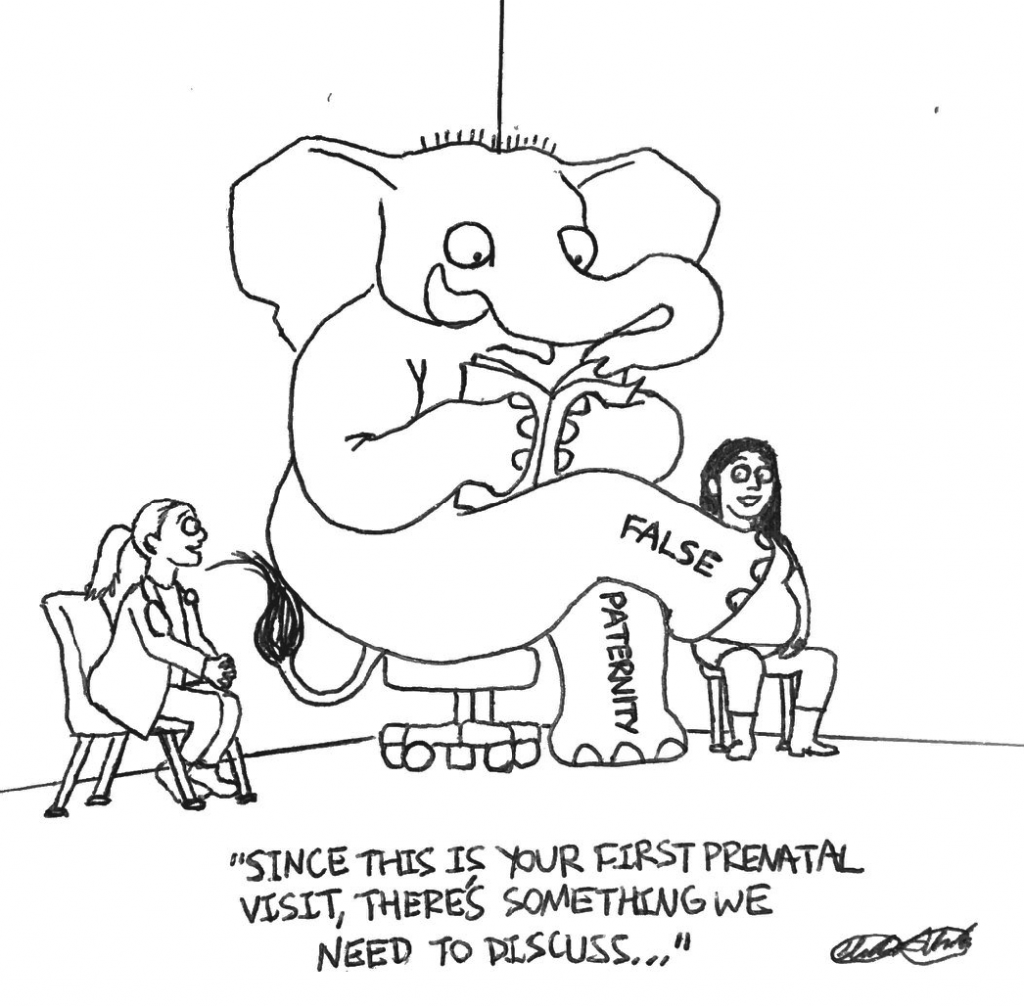

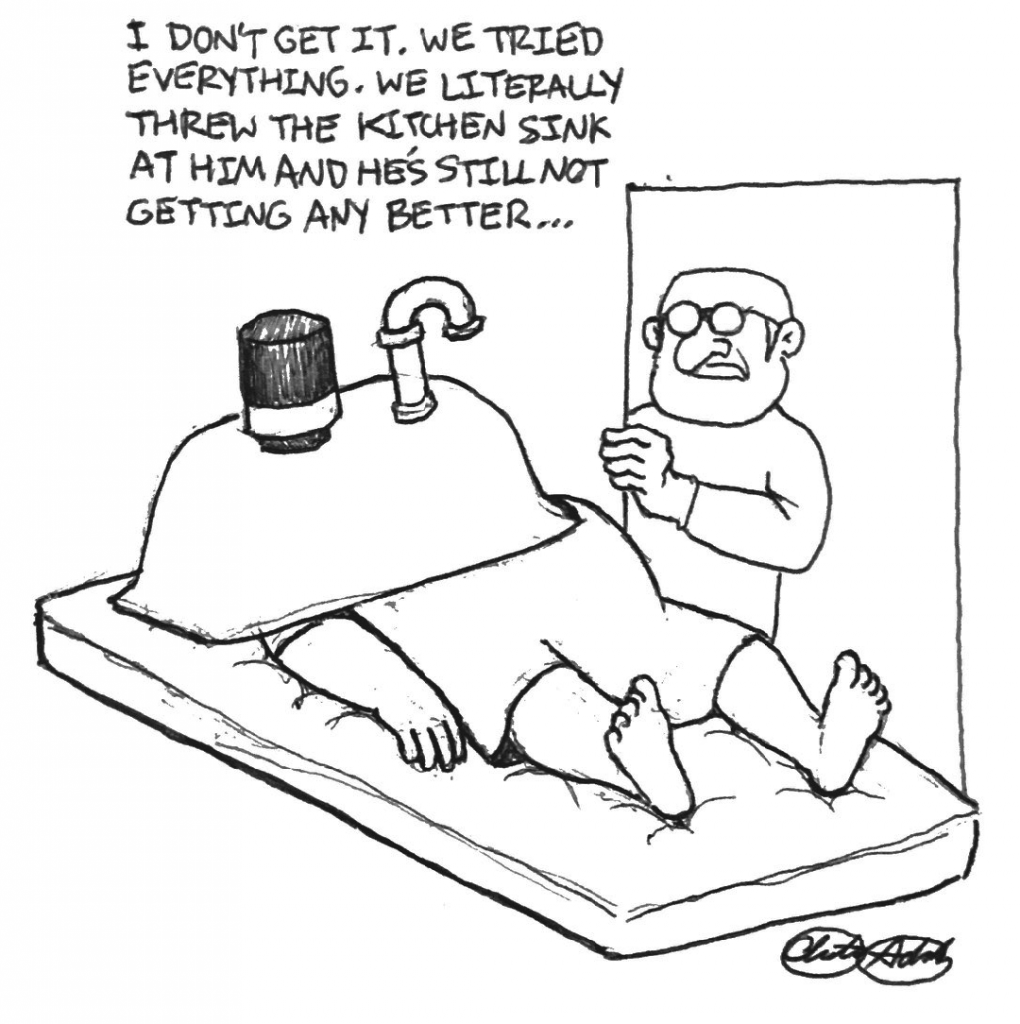

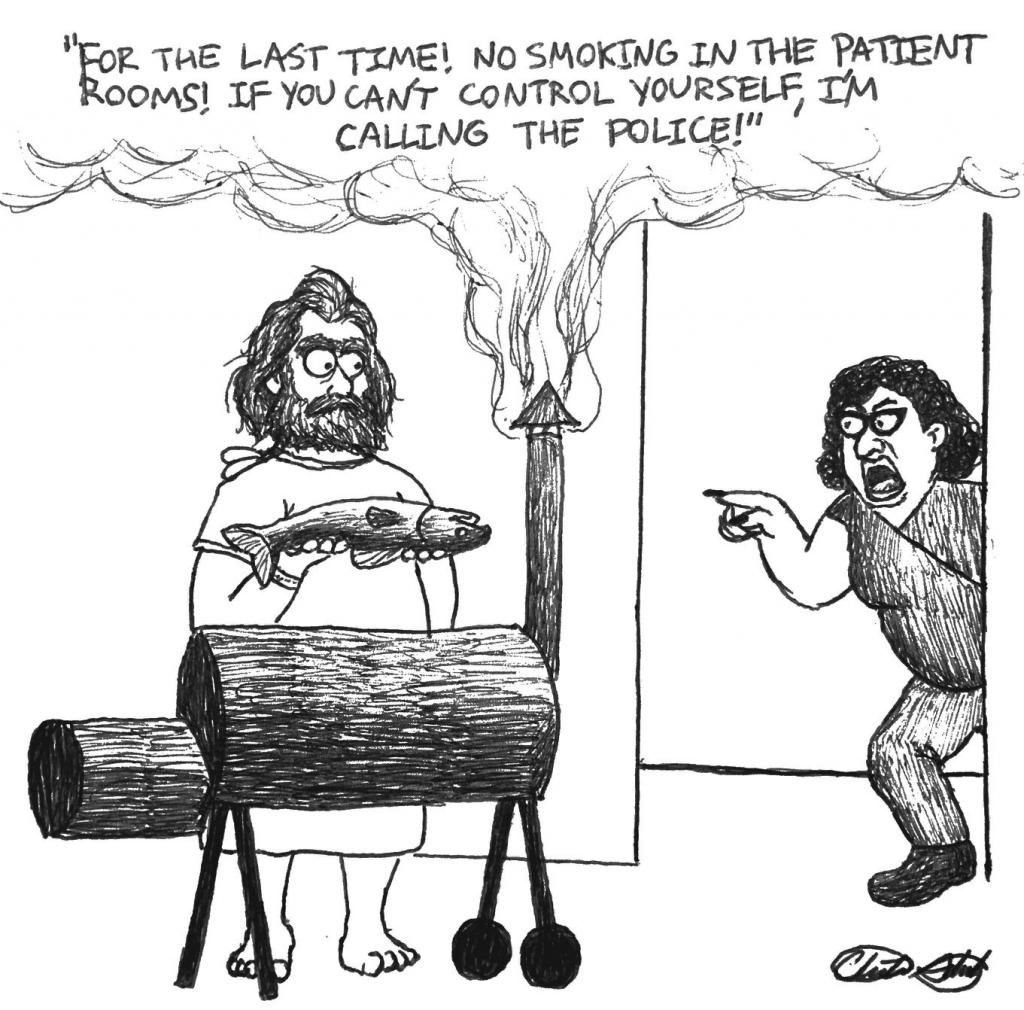

A Joke a Day

Every day I write a joke about the situations and larger than life personalities I encounter during medical school rotations. You can find more of my jokes on my Facebook page, “Stethojoke.”

Snoop

“You know who you remind me of, Ali,” the plastic surgeon standing opposite me in the operating room said. “Snoop Dogg. You sound just like him.”

Is he serious? Am I the only one who heard what he just said? My mind raced.

I was dumbfounded, but as a brown man living in Salt Lake City, I had had worse things said to me. I convinced myself he didn’t deserve a response. Just let it go, I told myself. He’s just an ignorant white guy.

He proceeded to call me “Snoop” for the next five hours, with the occasional “brotha” thrown in the mix. My cheeks grew visibly more flushed with each insult. By this point, I had to say something, but I couldn’t. I held my tongue, afraid my rage-fueled retaliation would make me out to be an “overly sensitive millennial.”

Throughout all of this, I tried to read his eyes. Was this his way of trying to relate? I soon realized that despite the surgical gown and mask I wore, the surgeon only saw brown skin and dark eyes staring back at him. There was nothing I could say. He had already assigned me a label and was treating me accordingly.

The rest of the case was a blur. I asked the team if they were okay with me stepping out to grab a quick bite to eat. But that was a lie. I was fasting for the month of Ramadan and knew that I still had a few hours before sunset.

I used to believe I knew how to thrive in white spaces, but there are days where no Oscar-worthy performance is enough. The clean-cut, charismatic routine I have woven into my being is at times exhausting, but I feel like it is something I must do, constantly contorting myself when necessary to fit into the tiny box of acceptable brown people.

After all, it was my ability to navigate white spaces that led me to areas such as the OR in the first place. But despite my best efforts, I have no control over how I’m perceived. There’s no on-off switch for my brownness that could have shielded me from the words of that plastic surgeon.

Words that I’ve heard far too often, burning like a thousand tiny papercuts, slowly wearing down the soul and creating a corrosive environment of self-doubt.

This is how I move through medicine: a trapezist walking the tightrope of white spaces. If I lose focus, even just for a second, I risk falling.

Rules for Attending Withdrawing Care Conferences

1. Under no circumstances note how the patient’s temples are grey with the same advancing pattern of color change as your father’s or how a strong man, just like your dad is, too, has been made powerless by his heart that always gave unconditional love.

2. Do not observe how his son clutches and wrings his baseball cap, just like the ones your brother always wears. Grant invisibility to his tears.

3. Forget that his wife, not unlike your own mother, does not cry.

4. Praise his daughter for saving his life with CPR, allowing the family time to say goodbye.

5. Zone out when the attending eulogizes the patient, remarking on how he is an incredible fighter, but his body was not up to this final match.

6. Use plain, straightforward language as you explain how and when he will die.

7. Reassure them he does not feel pain, but they should nevertheless hold his hand and tell him they love him and that they’ll be okay even though you can’t fathom that being true if this were your father.

8. Every time you sense tears welling in your eyes, imagine anything (i.e., the monotony of the reading you have to complete tonight, what you’re going to eat for lunch), anything to prevent you from crying. This is not your moment.

9. As best you can, shut out the wailing emanating from the family conference room you exited seconds ago.

10. Craft a list of personal rules intellectualizing the situation to prevent you from breaking down in fear of knowing your family is not immune to this situation.

11. Walk to the next patient room.

The Gift

Oh, the decision it must have been

To take the road less travelled;

Perhaps defying the wishes of remaining kin

To serve a cause much higher.

Mortal death could not end

The desire to teach and show

A group of eager students

The human body they must know.

Along a lifetime of medicine

Will bless the lives of scores.

In search of healing from grief and pain

Come the patients who enter the doors.

Remarkable the impact one choice can have

To awe, perplex, inspire.

The knowledge which will result

Will serve a cause much higher!

Takes a special person

To let others know them to the core;

Having them feel their beloved organs

Which promote life no more.

Head to toe and back to front

The body is slowly transformed

From its original purpose

So its students can be informed.

Amazing is the opportunity

Our donor to us has given

To learn, to feel, to touch, to know.

Our thirst for knowledge he has driven!

New appreciation has filled our souls

For the intricacies of the human body

Where structure determines function

And proteins serve as antibody.

Kidneys, muscles, and the bones of the body

Have taught us all so much.

Of the many ways of learning

One of the best is by touch.

Surely, words cannot express

The debt of gratitude we feel!

The gift one gave we must profess

Enables us to serve a cause much higher!

Differential Diagnosis: Climate Change

This “stethoscope” highlights the prodigious amount of medical waste produced by the healthcare system: nearly 7,000 tons of medical waste per day, amounting to roughly 3% of total U.S greenhouse gas emissions. It was created from expired/clean medical waste. I chose to create a stethoscope for its symbolism in healthcare. The stethoscope has become an elemental component of medical providers. It is a crucial diagnostic tool that has become nearly an extension of a healthcare provider’s body. The amazing part of this tool is its sustainability. A healthcare professional only really needs one or two stethoscopes throughout their career to care for their unending stream of patients. Patient livelihood is not put to harm, but environmental consciousness is preserved. The stethoscope is a paragon for the sustainability in medical tools that can be attained.

Worlds Apart

“I see the same skies through brown eyes that you see through blue. But we’re worlds apart, worlds apart. And you see the same stars through your window that I see through mine. But we’re worlds apart, worlds apart. And the mocking bird sings, in the old y’ander tree, twadiladee dee dah, dee dee dee.”

“Worlds Apart” from the Broadway musical Big River. Roger Miller and William Hauptman, 1985.

Jorgen uses abandoned books as his medium to create 3D representations of stories. This piece is from Aventures of Huckleberry Finn, which was read to him as a child.

PICU Rambling

Roses are red,

Some babies are blue,

Especially those with Tetralogy,

In the CICU.

A poem written on a whim by a senior resident and sub-intern on a busy spring Tuesday in the PICU.

What’s Worse

I’m not as sad about your dying.

I’m not as moved by your pain, your struggle

Your anoxic brain, your limp limbs, your artificial breaths

I’m not as sad about the soccer games you won’t play, the first kiss you won’t have

The heartbreak you may have been spared

I’m not as sad because you are no longer suffering.

But your dad

Your dad who sits by your lifeless side with his head in his hands

Your dad who is trying to remember how to breathe

Your dad who wishes you would just wake up, or that all of this is a terrible dream

Your dad who is worrying over what he did wrong, what more he could have done

Your dad who may be questioning his ability to go on, let alone support your Mom

Your dad who doesn’t know how he’ll survive tomorrow because you didn’t survive today.

Bye Bye Baby: Mom’s Perspective

Bye sweet baby

Bye bye

Or would it be better to wait out this trial?

Birth you completely

Have you live for the littlest while?

Months and months more of mutual agony

To have you suffer outside of me?

No, I’m sorry

There’s no need to make you cry baby

Bye sweet baby

Bye bye

Who Heals the Healer?

My wife and I got into an argument last night. I slept on the couch. I hate that. I missed holding her close and breathing in the smell of her hair. I woke up this morning and it was clear there was still an awkward tension in the air. I kissed her on the cheek and told her I loved her. She grudgingly said it back.

I know what she wants. She wants me to be able to stay home. To really sit down and talk through all of our “issues”. I can’t. Time is not on my side and I must go to work.

I tiptoe into my son Milo’s room while he sleeps in his crib. He has the softest skin and he sucks his tiny thumb just like I had done. I kiss his forehead; I try not to wake him up. My heart was stolen the day he was born. I hope he remembers and misses me while I am away.

I should want to stay home and be with Milo. I should want to stay and talk with my wife. There is a part of me that knows this, and halfheartedly wants to want it.

I pretend this doesn’t get to me, all the things I “should” feel, do, and be. I almost believe it.

I click my seatbelt and drive into work. Rain on the road makes the asphalt reflect the bright city lights. I can’t help but feel at home when I pull up to the hospital in the dark early hours.

The automatic glass doors of the hospital part, and I step into another dimension. Not one where my mother is going through chemo, or my wife is less than satisfied with our marriage, and I see my son so infrequently. Not one where my depression cripples my confidence. I step out of MY world. I become what THEY need.

As I throw my white coat over my light green scrubs and lace up my sneakers… I become invisible to the human heart. I am a symbol of strength. I offer hope. I heal. Even though I am less than whole.

“Dr. Tiller, your patient is ready in pre-op.”

And I go. I heal. I listen, teach, explain, and reassure. I cut, plate, suture, and cast. I do not cry, stress, show my pain, or hurt. With my white coat I must be invincible, and invisible. I am the healer.

But who will heal me?

Mooring

The guilt I carry

Drags at me like a

Sea anchor in a storm.

More weight flows in and

My scuppers are not enough.

Perhaps, then, I founder.

You come—an ocean in your eyes

And mouth ringed with earth, the

Sky upon your brow. Mortality

Pressing upon you all creation within

You, screaming culpability because your

Insensibility. Because you filled the

Mortal needle. And lay in stupor

Next to her choking warmth

Her machine is left for you but

Her dislodged intangible presses

—A weight I could not bear.

Your confession dribbles, but

Walking, we leave it behind.

Sharing knowledge of what

Has been together I see lengthening

Back behind us—tightening—

The bowed tails of

Our guilt flying,

Pulling us straight against

The stiffening breeze.

Step 1

To Astra in Clinic 6

Coloring, exclaiming of Mickey,

identical blonde hair to her nearby sisters,

the cotton leggings of girlhood,

she sits with legs askew in the unlearned

way of children.

But her boots belie her position.

Bright sunshine yellow,

securing the center around which

the waiting room revolves.

I sense the sublime; she carries the potential.

Does she feel the weight?

I seek ways to imbue them with magic.

Perfect shine providing protection from

snow, sleet, and society alike.

But my incantations are too late.

Scratches here and there

catch the fluorescent light.

Yet, the rubber still reflects

casting a halo of joy,

their armor unencumbered

by adult perceptions, opinions

With gratitude to a newfound star,

I rise and leave.

The Words We Use: Observations from Psych Rotation

This one’s loquacious

Someone else – in melancholy’s grip

Beware of the beguiling

They’ll slither into your own narcissism

Is that a pejorative?

This man does want to live!

Windows

In this composition, we see the truth in the cliche “beauty is in the eye of the beholder.” While the irises are undoubtedly captivating, the title of the piece calls attention to the light that passes through the pupil and informs the eye of the events unfolding before it. Each of these eyes belongs to a future physician who will be challenged to use the light entering to make difficult diagnostic decisions. However, as the variety in the texture and color of the irises suggest, each of the eyes will have unique experiences and challenges throughout their life.This digital composition was created for the Layers of Medicine course and depicts the irises of twenty-five of the members of the School of Medicine class of 2021.